Published September 5, 2023

Quick Facts:

- Alma’s Urban Agriculture Job Training Program in South Los Angeles has provided hands-on technical education in urban farming to more than 350 formerly incarcerated individuals since 2013.

- Between 2019 and 2022, ALMA trained 200 people, 45 of whom continued working at ALMA. Sixty percent of participants found employment following the three-month training program, including 30% who worked in construction jobs in which urban agriculture skills came in handy.

- These statistics compare favorably to White House findings that 75% of ex-prisoners remain unemployed one year after release.

- Ten percent of ALMA participants went on to pursue education such as community college, vocational school, or a GED.

- The main ALMA farm is based in Compton, South LA, where only 75% of food stores sell fresh produce (compared to 90% of stores in wealthier neighborhoods).

- 95.3% of customers at ALMA’s farm stand said that the food is better there than at other places in their neighborhood.

ALMA Backyard Farms, Compton, California © John T. Nguyen

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary

II. Background

III. Urban Agriculture Job Training Program

IV. Pepperdine University Research Study: Methodology

V. Results

VI. Conclusion

I. Executive Summary

ALMA Backyard Farms, a nonprofit organization based in Los Angeles, Calif., works to tackle food injustice and recidivism through urban farming initiatives that support formerly incarcerated individuals’ re-entry into society and food insecure communities. As part of its work, ALMA runs a job training program that provides individuals with prior justice system involvement with the skills and opportunities for future employment, including in urban farming, gardening, landscaping and carpentry. The three-month program has trained over 350 participants since 2013, including 200 between 2019 and 2022, during which time 60% of participants found employment after the program and 10% pursued more education.

ALMA Team Members © ALMA Backyard Farms

Alongside the urban farming projects, ALMA hosts a bi-monthly farm stand where its homegrown produce is sold. Located in what is considered a “food desert,”[1]An area where there are few to no convenient options for securing affordable, healthy foods – especially fresh fruits and vegetables. ALMA’s farm stand in Compton, Calif., sells its produce at below market rates, providing a service to a neighborhood where healthy, affordable, good quality food is not always available. During the COVID-19 pandemic, ALMA also provided grocery boxes to 250 families in nearby low-income communities.

A-Mark Foundation funded research by Pepperdine University graduate students looking into the impact of these programs on both the local communities surrounding the urban farms and the participants in the job training programs. The researchers used a mixed-method approach in their research, combining qualitative and quantitative data in order to analyze this impact.

Fourteen stakeholders associated with ALMA were surveyed, including occasional purchasers at the farm produce stand and ALMA staff members directly involved in the operation of the organization. Data analysis further evaluated the reach and impact of the organization in terms of community access to healthy food.

The interviews offered insight into the organizational culture at ALMA and its impact on its target beneficiaries as well as perceived challenges or barriers to its work and suggestions for improvement. Thirteen of the 14 interviewees praised the culture at the organization, and all 14 interviewees spoke about the positive impact the organization has on the local community and the lives of the formerly incarcerated.

Fewer interviewees talked about the barriers or challenges ALMA faces, but of those who did, the main challenges noted were related to land ownership / leases and staff capacity. Six interviewees responded to a question about ways in which ALMA could improve, mostly citing the desire to increase the organization’s operations.

A quantitative analysis of data shared with the students by staff at ALMA demonstrated the importance of the farm stand and pandemic grocery boxes to the local community. Almost all of the visitors to the farm stand said that the produce sold there is better than what is sold in their neighborhood stores, and over 60% said they eat more fruit and vegetables because of the farm stand. Almost half of the respondents visit twice a month and almost 50% travel less than five miles to get there.

Further information was provided directly to A-Mark Foundation from ALMA in relation to the impact of the Urban Agriculture Job Training Program.

II. Background

“In the beginning, we were driven by a deep desire to heal relationships harmed by the effects of incarceration, food insecurity, and re-entry. One of our genesis stories involved a mother recently released from incarceration who had not been present for her daughter during crucial developmental teen years. One way we discovered how their relationship can strengthen is by distributing food so families can prepare and share meals together.”

— ALMA Co-Founder Richard D. Garcia [2]Richard D. Garcia, “ALMA’s Philosophy of Growth,” https://www.almabackyardfarms.com, 2022, https://www.almabackyardfarms.com/endofyear

Incarceration, Poverty and Food Deserts: A Community Link

In 2023, the prison population in California consisted of 92,332 people in state prisons, 12,000 in federal prisons, and 78,000 in local jails, including 14,577 in LA County local jails.[3]California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, “Three Judge Quarterly Update – June 15 2023 Update to the Three-Judge Court,” cdcr.ca.gov, June 15, 2023, … Continue reading[4]Leah Wang, “How Many California Residents Are Locked Up?,” prisonpolicy.org, 2023, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/graphs/correctional_control2023/CA_incarceration_2023.html[5]Los Angeles Almanac, “Los Angeles County Jail System By the Numbers,” laalmanac.com, updated 2021, http://www.laalmanac.com/crime/cr25b.php Across the U.S., over 9.5 million people are released from state or local jails each year; 66% of them are rearrested within three years and over 50% are imprisoned again.[6]Liz Benecchi, “Recidivism Imprisons American Progress,” Harvard Political Review, August 8, 2021, https://harvardpolitics.com/recidivism-american-progress/ In California, 68.4% of released prisoners are rearrested within three years, with 44.6% of people being convicted of another crime.[7]Division of Correctional Policy Research and Internal Oversight, “Recidivism Report for Offenders Released From the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation in Fiscal Year … Continue reading According to statistics released by the White House, 75% of ex-prisoners across the United States remain unemployed one year after release.[8]The White House, “A Proclamation on Second Chance Month, 2022,” whitehouse.gov, March 31, 2022, … Continue reading

A systematic review published in Health and Justice indicated that “access to social support and housing; and continuity of case worker relationships … are key social and structural factors” to allow for successful re-entry into society post-incarceration.[9]Sacha Kendall, et al., “Systematic Review of Qualitative Evaluations of Reentry Programs Addressing Problematic Drug Use and Mental Health Disorders Amongst People Transitioning From Prison to … Continue reading Further research has determined that “skill development, mentorship, social networks, and the collaborative efforts of public and private organizations collectively improve the reentry experience.”[10]Annelies Goger, et al., “A Better Path Forward for Criminal Justice: Prisoner Reentry,” brookings.edu, April 2021, … Continue reading More specifically, urban farming or gardening programs have been shown to lower rates of recidivism among offenders who participate in prison-based or community service gardening programs.[11]See for example: Megan Holmes and Tina M. Waliczek, “The Effect of Horticultural Community Service Programs on Recidivism,” HortTechnology, Volume 29, Issue 4, July 9, 2019, … Continue reading

The Prison Policy Initiative notes that communities with a higher rate of incarceration have higher poverty rates.[12]Wendy Sawyer, “High Imprisonment Communities Have Higher Poverty Rates,” prisonpolicy.org, 2020, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/graphs/ny_imprisonment_poverty.html Research out of the University of Texas at San Antonio found that “formerly incarcerated individuals are more likely to live in areas with low access to healthy food retailers,” known as food deserts.[13]Alexander M. Testa, “Access to Healthy Food Retailers Among Formerly Incarcerated Individuals,” Public Health Nutrition, October 23, 2018, … Continue reading Disproportionally found in low-income areas, food deserts occur when “residents have few to no convenient options for securing affordable and healthy foods – especially fresh fruits and vegetables.”[14]The Annie E. Casey Foundation, “Food Deserts in the United States,” aecf.org, February 13, 2021, https://www.aecf.org/blog/exploring-americas-food-deserts A food swamp occurs when there is an “over-allocation” of unhealthy food such as fast food restaurants.[15]LX News, “ ‘Food Swamp’ vs. ‘Food Desert’: What’s the Difference?,” lx.com, June 20, 2022, … Continue reading

The Compton Chamber of Commerce notes that in some of the poorer areas of Los Angeles County, including Inglewood, Compton, Bell, East Los Angeles, and South Central Los Angeles, (all areas surrounding ALMA Backyard Farms’ Compton location), there are plenty of areas considered to be food deserts and food swamps.[16]Compton Chamber of Commerce, “Target Region: Great Compton Area,” comptonchamberofcommerce.org, accessed July 27, 2023, https://www.comptonchamberofcommerce.org/compton-nutrition-demographics Research published by the Chamber of Commerce found that only 75% of the food retail outlets in South LA sell fresh fruit and vegetables compared to 90% in West LA, home to some of the county’s wealthiest neighborhoods;[17]Los Angeles Times, “Mapping LA: Median Incomes,” latimes.com, accessed August 16, 2023, https://maps.latimes.com/neighborhoods/income/median/neighborhood/list/ and shoppers in South LA have half the choice of their West LA counterparts and are more likely to be sold spoilt or damaged produce.[18]Compton Chamber of Commerce, “Target Region: Great Compton Area,” comptonchamberofcommerce.org, accessed July 27, 2023, https://www.comptonchamberofcommerce.org/compton-nutrition-demographics

ALMA Backyard Farms’ Role in the Community

ALMA Backyard Farms is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization founded in Los Angeles in 2013 by Richard D. Garcia and Erika L. Cuellar with a goal to repurpose urban land into productive urban farms. Through their Urban Agriculture Job Training Program, the organization “focuses on restoring the lives of formerly incarcerated women & men through hands-on technical education in urban agriculture, carpentry & landscaping,” giving the participants “the chance at attaining gainful employment and becoming self-sufficient.”[19]ALMA Backyard Farms, “Homepage,” almabackyardfarms.com, accessed July 24, 2023, https://www.almabackyardfarms.com

In addition to the training program, ALMA also runs a bi-weekly farm stand in Compton, that provides healthy, affordable produce to the local community, hosts summer camps and other educational workshops and, during the COVID-19 pandemic, provided 250 households with grocery kits.[20]For more information, see the ALMA Backyard Farms website at www.almabackyardfarms.com In 2022, ALMA grew and distributed over 125,000 pounds of produce, grown over three acres of urban land in Compton, East Los Angeles, Riverside and San Pedro.[21]ALMA Backyard Farms, “End of Year Letter,” almabackyardfarms.com, 2022, https://www.almabackyardfarms.com/endofyear

To analyze the reach and impact of this organization, A-Mark Foundation partnered with Pepperdine University’s School of Public Policy to conduct a survey of stakeholders involved with ALMA alongside an analysis of self-reported data. Four masters students, Kirill Strakhov, Leilani Jimenez, Jaimie Park and Alex DeSantis, conducted the research under the supervision of their advisor, Professor Marlon Graf, PhD. Additional data was provided directly to A-Mark Foundation from ALMA.

The survey results are explored below. The Pepperdine team’s presentation of their results and policy analysis is titled, “Final Capstone in Collaboration with ALMA Backyard Farms.”

Founders Richard D. Garcia and Erika L. Cuellar at ALMA Backyard Farms, Compton © Leroy Hamilton

III. Urban Agriculture Job Training Program

According to self-reported data provided by ALMA to A-Mark Foundation, ALMA’s Urban Agriculture Job Training Program has provided hands-on technical education in urban farming to more than 350 formerly incarcerated individuals in Los Angeles County since the organization’s inception in 2013. Training program participants have gone on to work as a counselor for domestic abuse victims, a lab technician, a truck driver, a construction foreman, and more. They have stories about reconnecting with their children, starting families, and maintaining sobriety.

Between 2019 and 2022, ALMA trained 200 people, 45 of whom continued working at ALMA. Sixty percent of participants found employment following the three-month training program, including 30% who worked in construction jobs in which urban agriculture skills came in handy. Ten percent of participants went on to pursue education such as community college, vocational school, or a GED. Participants in the training program between 2019 and 2022 ranged in age from 18 to 60; 52% were Latino, 35% Black, 10% white, and 3% Asian.

“Working on the new farm project gives me a sense of hope that no matter what I encounter in life I can get through it. In the past, it was hard for me to connect with positive people because of the lifestyle I was living.”

— Dennis, ALMA training participant who joined the program after spending 27 years in prison

While 70% of participants in ALMA’s program have gone on to educational programs or entered the workforce, data from the White House notes that 75% of “people who were formerly incarcerated are still unemployed a year after being released.”[22]Joseph R. Biden, “A Proclamation on Second Chance Month, 2022,” whitehouse.gov, March 31, 2022, … Continue reading

In 2023, ALMA set a goal to train 50 program participants. It also launched a partnership with Homeboy Industries, a nonprofit that helps former gang members, to train formerly incarcerated or gang-involved youth between the ages of 14 and 22.

IV. Pepperdine University Research Study: Methodology

The student researchers used a mixed-method approach to their research, combining qualitative narrative storytelling through interviews with ALMA stakeholders and quantitative data analysis to further determine the impact and reach of the organization.

Prior to commencing the study, the research project was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Pepperdine University and the students undertook the University’s applicable Human Subjects Training requirements.

After receiving informed consent from the participants, the Pepperdine team interviewed 14 individuals involved with ALMA. Participants included two representatives from the ALMA board, one employee, two volunteers, four customers / vendors / promotional partners, and three funding partners. The nature of the involvement of two stakeholders was not listed in the interview transcripts.

The interview consisted of 14 open-ended questions designed to provide direct insights into the mission, culture, barriers experienced by, and impact of, the organization, as well as ideas for improvement.

To complete the quantitative aspect of the study, the researchers received self-reported data from ALMA staff via email. Identifiers or keys were stored in a separate, password-protected, or encrypted file, and no highly sensitive information was shared outside of the study group. The data covered the types of produce sold on the farm stand as well as information about the pandemic-era grocery box service and the opinions and experiences of customers visiting the farm stand.

V. Results

A. Qualitative Research Surveys

Throughout the 14 interviews undertaken by the students, the interviewees mostly expressed positive views of the ALMA program, with minor suggestions for improvements to bolster the program's long-term success.

The key points made by the interviewees can be summarized as follows:

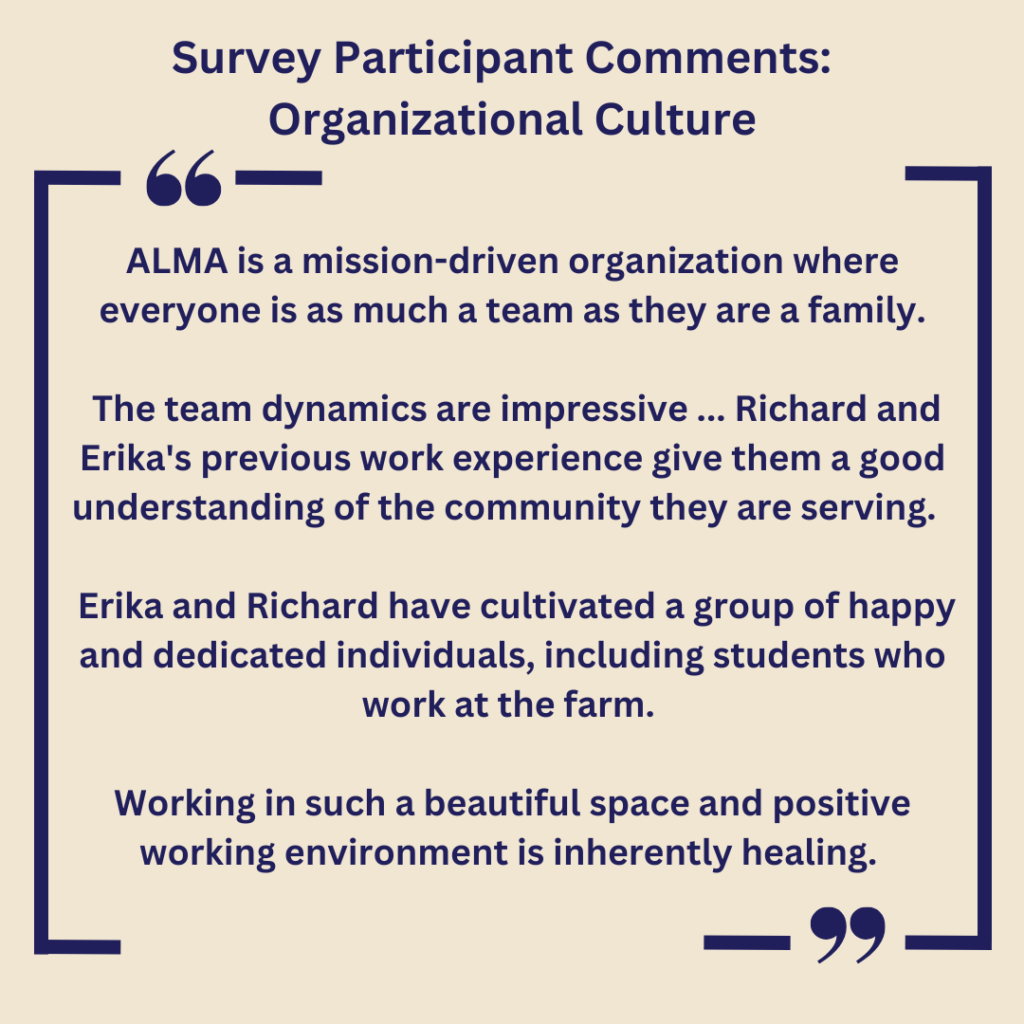

I. Organizational Culture

Thirteen of the 14 interviewees talked about the positive nature of ALMA’s organizational culture.

One interviewee appreciated the “non-judgmental, welcoming approach” that Alma Farms takes with formerly incarcerated individuals, recognizing the need to treat them as whole people rather than just a label, while another said that ALMA was “like a family, with everyone being supportive and empowering.”

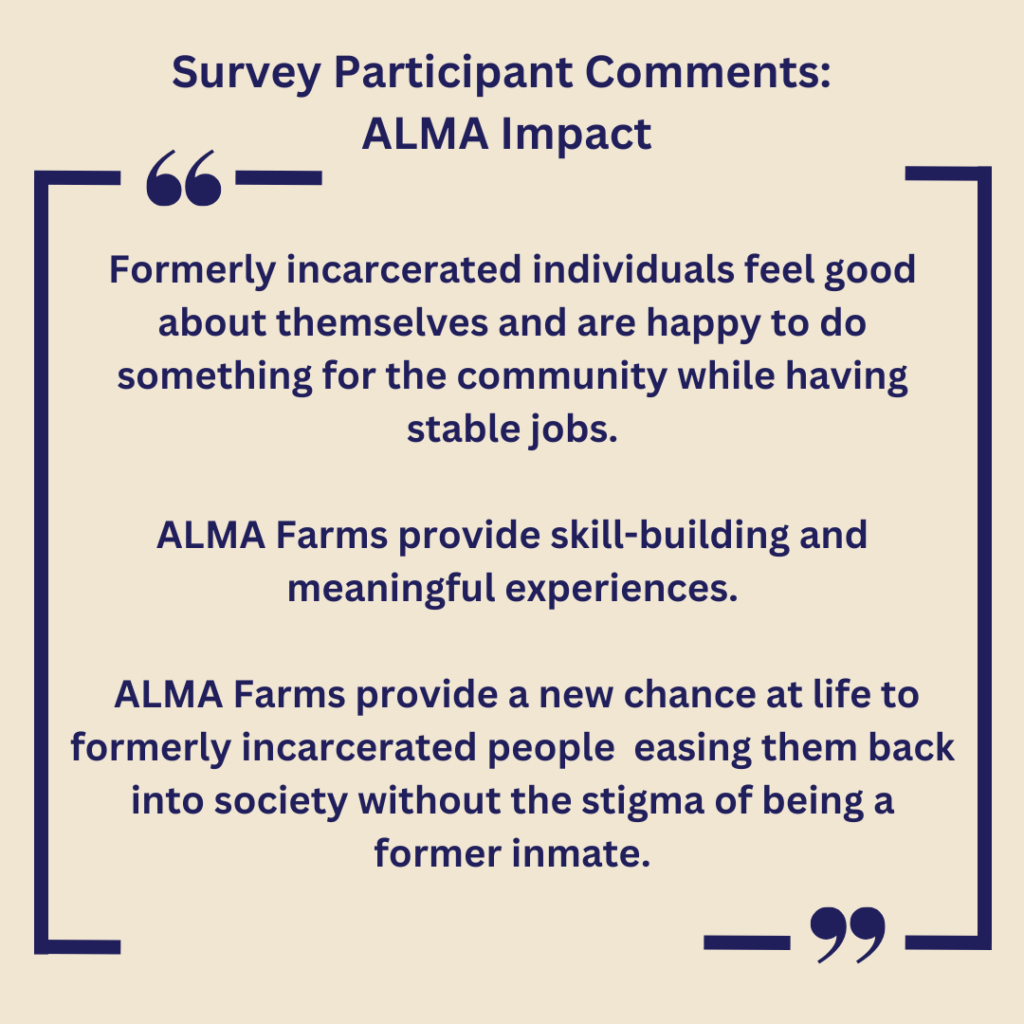

II. Impact

All interviewees were very impressed with the impact ALMA makes in the local community.

Many commended the organization for creating a safe space for everyone, connecting people from different backgrounds, engaging with local schools and churches, and providing job opportunities.

According to one interviewee, ALMA demonstrates that positive experiences can be had in Compton which fosters local pride in a community still battling negative media coverage and stigmas of the past.

Other interviewees noted the importance of ALMA’s provision of affordable, good quality produce to a community that has fewer quality food retailers, as well as educating people on how to grow and cook it.

In terms of helping formerly incarcerated individuals, 12 of the 14 interviewees specifically praised ALMA for their work in this area with one respondent noting that the ALMA model is “successful in combating high rates of recidivism and improving community outcomes … [fostering] social inclusion and trust toward food security by giving back to the community and providing therapeutic options while working on a farm.” Another noted that ALMA’s work is crucial, and that the “farm and the process of planting, growing, harvesting, and creating compost are real things that happen daily and provide powerful metaphors for people rebuilding their lives.”

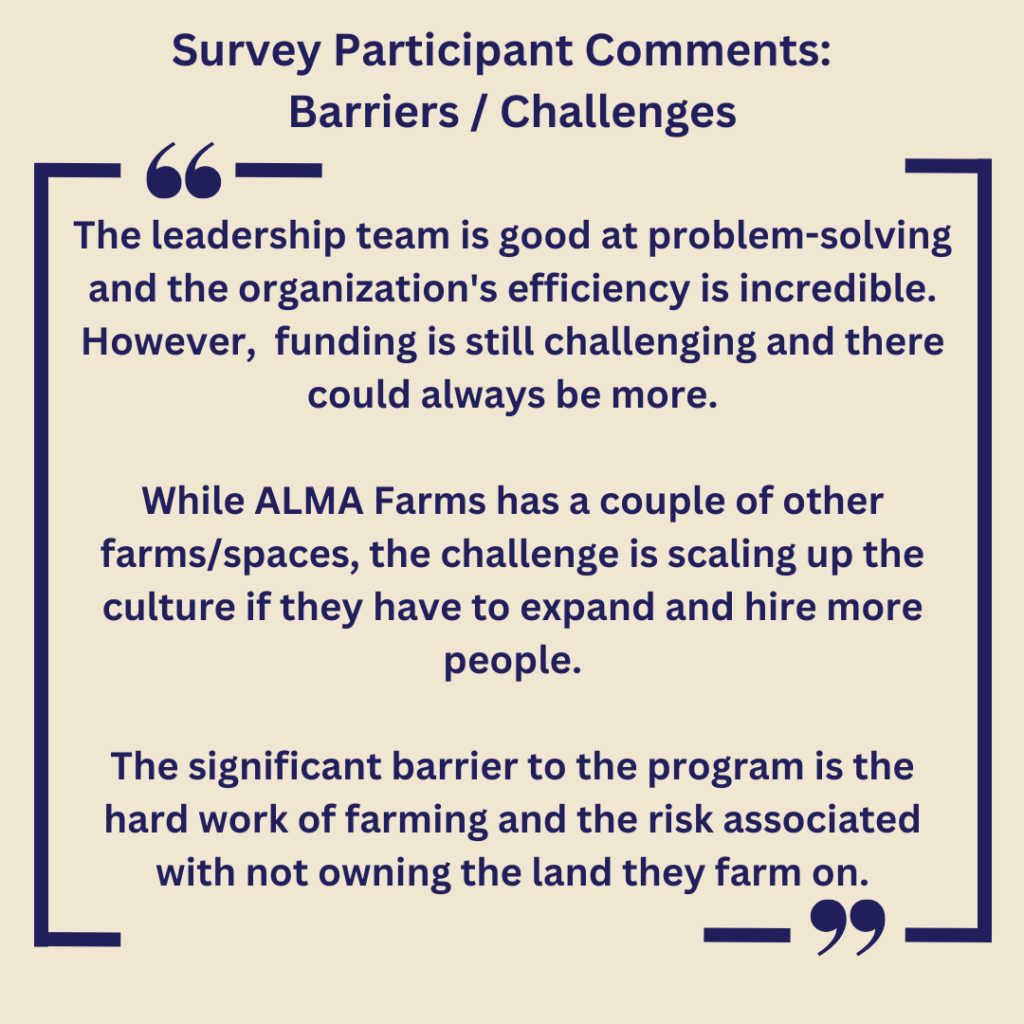

III. Barriers / Challenges

Some respondents stated that there are no barriers or challenges to address. Other respondents identified a number of potential barriers that ALMA faces.

Four interviewees raised the issues of land ownership, permits and city ordinances. As of July 2023, ALMA does not own any of the land that they farm and according to one interviewee, “there is no playbook for setting up an urban farm.” As a result, permits can take longer as there is no procedure in place, and there are added complications of working with the city, council and local parties in relation to rental agreements, utilities and other policies.

Another challenge relates to employment, staff capacity and expansion. According to one interviewee there is a low turnover of staff which is positive, however they note that if the option to expand were to arise, there is limited budget available to do so. Furthermore, it was noted that hiring, when needed, can be a challenge and staff capacity has previously been a concern. This in turn limits ALMA’s ability to reach a larger number of residents in the immediate area of the Compton urban farm. Another respondent advised caution when looking to expand, asking, “who will pick up the slack in work, vision, community, and inspiration when external factors change?”

Demand for produce is also a challenge ALMA faces, according to one interviewee. Often the farm stand sells out within an hour, meaning some people have to be turned away. There is a continual risk that ALMA may not have enough food for everyone and the potential risk of the farms not being productive enough to allow them to have a reliable food source.

Finally, one interviewee said that societal stigma and the current criminal justice system are potential barriers to ALMA although they did not elaborate how.

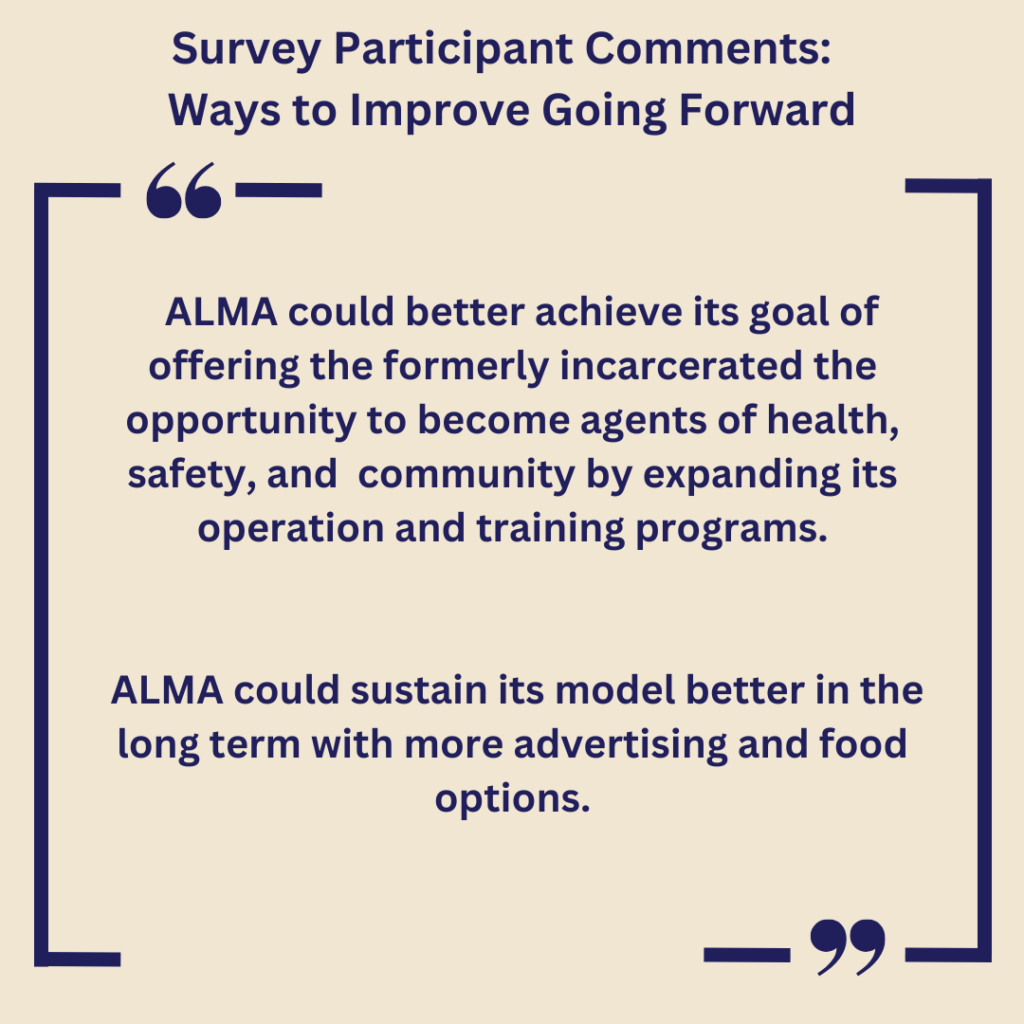

IV. Ways to Improve Going Forward

Six of the interviewees made suggestions for how ALMA can improve going forward.

Four wanted the organization to increase its presence in the community by scaling operations to reach more individuals, although two did raise concerns about doing this too quickly without necessary resources to cope.

One interviewee suggested that ALMA should increase advertising and food options, specifically by adding hot food options to bring people to the farm. Another interviewee suggested that ALMA needs to prioritize intersecting restorative justice and urban farming more smoothly and another said that ALMA needs to improve the way it tells the team members' stories.

The student research team concluded: “To sum up, ALMA Backyard Farms is clearly and intentionally making a positive difference in the communities that they serve. The relationships that Richard and Erika have fostered have led to meaningful connections that support the long-term health and sustainability of the program. ALMA Backyard Farms can strengthen its operation with the possible implementation of the feedback from data collected in these interviews.”

B. Quantitative Data Analysis

After final approval from Pepperdine’s Institutional Review Board, the researchers gathered data by email from stakeholders involved in the ALMA programs.

ALMA sells produce grown on their farms at their bi-monthly Farm Stand in Compton, CA. After judging market price, ALMA drops the price of their produce by between 50¢ and $1, ensuring that local communities have access to affordable, healthy produce. Most produce sold at the farm stand is priced at $1 - $2 per pound or per unit, depending on the type of produce.

In 2022, the top yielding crop grown by ALMA was kale, closely followed by tomatoes, squash and collard greens. Other produce grown that year included: bananas, broccoli, cucumbers, eggplants, peppers and watermelons.

Farm Stand Produce © Rob Eshman / A-Mark Foundation

ALMA employs between five and ten part- and full-time trainees to sell or distribute 90% of produce grown at the urban farms. The remaining 10% is shared with partner agencies serving low-income communities. Partner agencies either receive large amounts of the same crops to generate bulk meals, and other partners create smaller diverse meals using bunches of produce like kale, radish and celery. Partners include: Bracken’s Kitchen (Orange County), Curt’s Kitchen (San Pedro), San Pedro Meals on Wheels, Compton Food Bank, Project Q, Alexandria House, and Community Fridges.

During the pandemic, ALMA provided 250 households in low-income communities with grocery kits that included produce, prepared food, and beverages. Ninety kits were distributed in the Compton area, with the rest distributed in Central LA, Koreatown, Playa Del Rey, San Pedro and Long Beach.

Of the 250 households who received the grocery kits during the pandemic, 62% were returning beneficiaries of the scheme. Self-reported accounts of race or ethnicity show diversity across recipients; approximately 72.4% identified as Latino / Latina / “Latinx,” 18.8% identified as Black, 3.3% as Asian/Pacific Islander and 1.7% as white.

When analyzing data from a July 2020 ALMA survey of visitors to the farm stand, the students found that 48.8% of respondents visit every other week, with 18.6% saying they visit once a month and 10.9% visiting less than once a month; 21.7% were on their first visit.

When asked about the length of time spent at the farm, the majority of the respondents (67.4%) said that they usually just shop and go. 12.4% meet up with friends and 10.9% come to hangout for the day. The remaining 9.3% stay for various other reasons, mainly relating to the community and other nearby activities.

When asked how far they traveled to the farm stand, the majority of respondents (48.8%) said less than five miles. 37.2% said between five and 10 miles, and 14% traveled further than 10 miles. Data from 2022 found that some visitors to the farm stand traveled almost 25 miles from Altadena and Pasadena while others drove approximately 30 miles from Santa Ana and Orange County.

Of the visitors to the farm stand in July 2020, 67.4% said that they have tried new or unfamiliar fruits or vegetables from the farm stand, and 62% say that they now eat more fruit and vegetables as a result of coming to the farm stand. When asked about the quality of the produce, 79.8% of respondents said that the food is much better compared to other places in their neighborhood.

When asked, What’s one thing you’d improve or make better at ALMA? nearly half of the respondents (49%) said they would not change a thing. 34% indicated that they wanted more of everything - more variety and volume of foods, more hours and days/weeks open, more farmland, more tables, more live music and more support from organizations in the neighborhood. Other respondents recommended advertising, marketing and more promotion to Compton residents or calendar notices to existing attendees, as well as the re-opening of the San Pedro farm stand (closed due to permitting issues) and more children’s activities.

VI. Conclusion

For the past decade, ALMA Backyard Farms has worked to reduce recidivism rates by providing job training opportunities for over 350 formerly incarcerated individuals while also providing good quality, healthy and affordable food to the local community.

According to ALMA data, 70% of participants in ALMA’s training program have gone on to educational programs or entered the workforce. This compares favorably to data from the White House that finds that 75% of ex-prisoners remain unemployed one year after release.

Data analysis shows that the ALMA farm stand is very popular with the local community. Almost 50% of attendees traveled less than five miles to attend, and when asked what they would change about the farm stand, almost 50% said nothing, and another 34% said they wanted more of everything that is already provided. Furthermore, it is generally agreed that the quality of produce sold at ALMA’s farm stand is better than other neighborhood options, and, after attendance at the farm stand, the majority of attendees also noted that they now eat more fruit and vegetables.

From the stakeholder interviews, it is clear that ALMA is making a positive difference to the communities they serve, leading the student researchers to conclude:

“The excellence in leadership, integrity, value, and culture demonstrated by ALMA provides evidence of how a holistic approach to designing a restorative justice model can inform a dynamic model that re-humanizes the formerly incarcerated through community and offers the opportunity to build on existing skills and reenter the workforce. … To implement local solutions in the immediate area of Los Angeles, we view ALMA’s current model as an example of an organization that successfully and directly addresses recidivism and food injustice in low-income neighborhoods. …

Answers from interviewees agreed on the tangible effects of ALMA’s program. Success was evident locally, systemically, and through individual testimonials of witnessing the lives of incarcerated individuals transformed. The holistic approach that ALMA uses to understand systemic challenges and address recidivism and solutions according to this context is evident in the implementation of their program’s regenerative model. …

By increasing access to healthy produce in a historically disadvantaged area that has historically experienced food inequity, ALMA is solving one issue. The culture and environment ALMA maintains through its interpersonal communications, inclusivity, environmental stewardship, accessibility, and spiritual practice make it excel beyond an ordinary food equity project.”

Team Photo at the Farm Stand, Compton © ALMA Backyard Farms

We hope that this survey will be helpful to policy makers and non-profit groups working on recidivism and food insecurity in Los Angeles and beyond.

References

| ↑1 | An area where there are few to no convenient options for securing affordable, healthy foods – especially fresh fruits and vegetables. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Richard D. Garcia, “ALMA’s Philosophy of Growth,” https://www.almabackyardfarms.com, 2022, https://www.almabackyardfarms.com/endofyear |

| ↑3 | California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, “Three Judge Quarterly Update – June 15 2023 Update to the Three-Judge Court,” cdcr.ca.gov, June 15, 2023, https://www.cdcr.ca.gov/3-judge-court-update/ |

| ↑4 | Leah Wang, “How Many California Residents Are Locked Up?,” prisonpolicy.org, 2023, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/graphs/correctional_control2023/CA_incarceration_2023.html |

| ↑5 | Los Angeles Almanac, “Los Angeles County Jail System By the Numbers,” laalmanac.com, updated 2021, http://www.laalmanac.com/crime/cr25b.php |

| ↑6 | Liz Benecchi, “Recidivism Imprisons American Progress,” Harvard Political Review, August 8, 2021, https://harvardpolitics.com/recidivism-american-progress/ |

| ↑7 | Division of Correctional Policy Research and Internal Oversight, “Recidivism Report for Offenders Released From the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation in Fiscal Year 2017-18,” cdcr.ca.gov, April 2023, https://www.cdcr.ca.gov/research/wp-content/uploads/sites/174/2023/04/Recidivism-Report-for-Offenders-Released-in-Fiscal-Year-2017-18.pdf |

| ↑8 | The White House, “A Proclamation on Second Chance Month, 2022,” whitehouse.gov, March 31, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2022/03/31/a-proclamation-on-second-chance-month-2022/ |

| ↑9 | Sacha Kendall, et al., “Systematic Review of Qualitative Evaluations of Reentry Programs Addressing Problematic Drug Use and Mental Health Disorders Amongst People Transitioning From Prison to Communities,” Health and Justice, 6, March 2, 2018, https://healthandjusticejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40352-018-0063-8 |

| ↑10 | Annelies Goger, et al., “A Better Path Forward for Criminal Justice: Prisoner Reentry,” brookings.edu, April 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/a-better-path-forward-for-criminal-justice-prisoner-reentry/ |

| ↑11 | See for example: Megan Holmes and Tina M. Waliczek, “The Effect of Horticultural Community Service Programs on Recidivism,” HortTechnology, Volume 29, Issue 4, July 9, 2019, https://journals.ashs.org/horttech/view/journals/horttech/29/4/article-p490.xml or Rachel Jenkins, “Landscaping in the Lockup: The Effect of Gardening Programs on Prison Inmates,” arcadia.edu, May 3, 2016, https://scholarworks.arcadia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=grad_etd |

| ↑12 | Wendy Sawyer, “High Imprisonment Communities Have Higher Poverty Rates,” prisonpolicy.org, 2020, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/graphs/ny_imprisonment_poverty.html |

| ↑13 | Alexander M. Testa, “Access to Healthy Food Retailers Among Formerly Incarcerated Individuals,” Public Health Nutrition, October 23, 2018, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/public-health-nutrition/article/access-to-healthy-food-retailers-among-formerly-incarcerated-individuals/964851BE4404E2FD8B9B0D11F6B90B9C |

| ↑14 | The Annie E. Casey Foundation, “Food Deserts in the United States,” aecf.org, February 13, 2021, https://www.aecf.org/blog/exploring-americas-food-deserts |

| ↑15 | LX News, “ ‘Food Swamp’ vs. ‘Food Desert’: What’s the Difference?,” lx.com, June 20, 2022, https://www.lx.com/social-justice/food-swamp-vs-food-desert-whats-the-difference/54482/ |

| ↑16, ↑18 | Compton Chamber of Commerce, “Target Region: Great Compton Area,” comptonchamberofcommerce.org, accessed July 27, 2023, https://www.comptonchamberofcommerce.org/compton-nutrition-demographics |

| ↑17 | Los Angeles Times, “Mapping LA: Median Incomes,” latimes.com, accessed August 16, 2023, https://maps.latimes.com/neighborhoods/income/median/neighborhood/list/ |

| ↑19 | ALMA Backyard Farms, “Homepage,” almabackyardfarms.com, accessed July 24, 2023, https://www.almabackyardfarms.com |

| ↑20 | For more information, see the ALMA Backyard Farms website at www.almabackyardfarms.com |

| ↑21 | ALMA Backyard Farms, “End of Year Letter,” almabackyardfarms.com, 2022, https://www.almabackyardfarms.com/endofyear |

| ↑22 | Joseph R. Biden, “A Proclamation on Second Chance Month, 2022,” whitehouse.gov, March 31, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2022/03/31/a-proclamation-on-second-chance-month-2022/ |