Updated February 7, 2023 | Published December 21, 2022 | Take the quiz

Quick Facts:

- The debate about how much influence Supreme Court law clerks have over justices dates back to the 1950s. One recent study found that “clerks exert a modest but statistically significant effect on how justices vote.”

- Some say the law clerks have little influence due to their youth and legal inexperience. A 1998 investigation by USA Today “found few signs of ideological manipulation by today’s clerks.”

- Law clerks perform research, vet cases, and help draft opinions.

- Ten former law clerks went on to become Supreme Court justices. Others became members of the House, presidents of universities and a U.S. Secretary of State, among other influential positions. Some command up to $700,000 in salaries and bonuses when they join prestigious law firms following their clerkships.

- Law clerks for the sitting Supreme Court Justices have come predominantly from Yale (23.3%) and Harvard (22.9%)

- All of the sitting justices went to law school at Harvard or Yale except Amy Coney Barrett, who went to Notre Dame.

- In the 2022-2023 term, there are 38 law clerks. An estimated 84% of the law clerks are white and 66% are male.

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary

II. The Role of Law Clerks

III. Demographics

IV. Influence

V. Law Clerks for Sitting Justices

VI. Conclusion

I. Executive Summary

Supreme Court law clerks gained national attention in May 2022 amid speculation about the source of a leak revealing that the Court was poised to overturn Roe v. Wade. The 36 law clerks hand-selected by the justices make up approximately half of the estimated 70 people who have access to draft opinions, putting them in the spotlight of the investigation to find the leak.[1]Jessica Gresko, “Court That Rarely Leaks Does So Now in Biggest Case in Years,” apnews.com, May 3, 2022, … Continue reading

While the general public may have previously given little thought to the role of Supreme Court law clerks, the debate about how much influence they might wield over the outcome of cases dates back at least 65 years. A 1957 article in U.S. News and World Report raised the question of whether “the influence of these young law clerks—some not yet admitted to the bar—is reflected in Court opinions.”[2]Todd C. Peppers, Courtiers of the Marble Palace, Stanford Law and Politics, 2006

Some argue that the influence of clerks is limited by the fact that they are usually inexperienced lawyers and likely share similar ideologies as the justices who hired them. Even still, the clerks may retain some ability to impact the workings of the Court, such as recommending which cases are heard and deciding what information the justices are given.[3]Mark C. Miller, “Law Clerks and Their Influence at the US Supreme Court: Comments on Recent Works by Peppers and Ward,” Law & Social Inquiry, April 22, 2014, … Continue reading This report examines what is known about the Supreme Court law clerks, followed by details about the clerks chosen by the current justices.

II. The Role of Law Clerks

Ten former law clerks went on to become Supreme Court justices, including six members of the current Court: John G. Roberts, Jr., Elena Kagan, Neil M. Gorsuch, Brett M. Kavanaugh, Amy Coney Barrett, and Ketanji Brown Jackson.[4]Supreme Court of the United States, “FAQs – Supreme Court Justices,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/faq_justices.aspx. Other clerks have gone on to serve as U.S. Secretary of State, U.S. Attorney General, ambassadors, members of the House of Representatives, presidents of universities, and in other positions of influence, including at least one Fox News host (Laura Ingraham).[5]Todd C. Peppers, Courtiers of the Marble Palace, Stanford Law and Politics, 2006 Lawyers who complete a clerkship at the Supreme Court are in high demand and can reportedly be paid up to $700,000 in salaries and bonuses when they are hired by major law firms.[6]Roy Strom, “SCOTUS Clerks Have Everything to Lose as Leak Probe Launches,” Bloomberg Law, May 3, 2022, … Continue reading

The first Supreme Court law clerk was hired in 1882, nearly 100 years after the Court was formed. Since the 1970s, each associate justice can hire four law clerks per term. While the chief justice can choose five, Chief Justice Roberts has had just four clerks every year except for his first term. While the number of clerks is unchanged, the number of opinions issued by the Court has dropped significantly. In 1975, the Court had 160 signed opinions, a ratio of 4.4 cases per clerk.[7]Christopher Kromphardt, “The Supreme Court Has More Clerks and Less Work Than 50 Years Ago,” Washington Post, May 16, 2022, … Continue reading In 2021, the Court had 58 signed opinions, about 1.6 per clerk.[8]Angie Gou, Ellena Erskine, and James Romoser, “Stat Pack for the Supreme Court’s 2021-22 term,” SCOTUS Blog, July 1, 2022, … Continue reading The number of petitions for the Court to hear a case, by contrast, has increased from 3,940 in 1975 to between 7,000 and 8,000 today.[9]Supreme Court of the United States, “The Supreme Court at Work,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 17, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/courtatwork.aspx. The Court grants review and hears oral arguments in about 80 cases annually.[10]Public Information Office of the Supreme Court of the United States, “A Reporter’s Guide to Applications Pending Before the Supreme Court of the United States,” supremecourt.gov, September … Continue reading

The law clerks serve for one year and are generally recent graduates from top law schools who have completed clerkships with judges at lower federal circuit and district courts, usually in the federal court of appeals.[11]Mark C. Miller, “Law Clerks and Their Influence at the US Supreme Court: Comments on Recent Works by Peppers and Ward,” Law & Social Inquiry, April 22, 2014, … Continue reading

The justices set their own criteria for choosing law clerks. Legal scholars note that, since the 1990s, justices have tended to hire clerks who worked for other judges with similar ideological views, although the practice began ramping up in the 1970s.[12]Lawrence Baum, “Hiring Supreme Court Law Clerks: Probing the Ideology Between Judges and Justices,” Marquette Law Review, 2014, … Continue reading The late Antonin Scalia, an associate justice from 1986 to 2016, often hired one “counter-clerk” – meaning a law clerk with a more liberal bent – to offer balance to his considerations.[13]Gil Seinfeld, “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Reflections of a Counterclerk,” Michigan Law Review First Impressions, 2016, … Continue reading Sitting justice Clarence Thomas, on the other hand, famously said, “I won’t hire clerks who have profound disagreements with me. It’s like trying to train a pig. It wastes your time, and it aggravates the pig.”[14]Adam Liptak, “A Sign of the Court’s Polarization: Choice of Clerks,” nytimes.com, September 6, 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/07/us/politics/07clerks.html.

Law clerks perform legal research, formulate questions to use during oral arguments, and help draft opinions. Most justices participate in what is called the “cert pool,” which is an agreement for the petitions for certiorari (requests for the Court to review a case) to be split among all the law clerks to review, summarize, and make a recommendation on whether to grant a petition for certiorari (accept the case).[15]United States Courts, “Supreme Court Procedures,” uscourts.gov, accessed November 3, 2022, … Continue reading Since the Supreme Court as an institution is notoriously secretive, much of what the law clerks do has been teased out by interviews with former clerks. It appears that clerks play a role in writing the judicial opinions, but how much influence they have over the outcomes remains unclear.[16]Adam Bonica, Adam Chilton, Jacob Goldin, Kyle Rozema, and Maya Sen, “Legal Rasputins? Law Clerk Influence on Voting at the U.S. Supreme Court,” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, … Continue reading

Since at least the mid-1990s, all Supreme Court law clerks previously worked for another judge for a year or more. An analysis by Sarah Isgur, a Justice Department spokesperson in the Trump administration, found that, "From 1996 to 2016, 16 percent of Supreme Court clerks had clerked for more than one judge before making it to SCOTUS." In the following years, "that number has skyrocketed to 61 percent." Isgur noted, for example, that 20 percent of Ruth Bader Ginsberg's clerks had spent more than a year clerking for a lower court judge prior to 2016; in her last four years as a justice, almost 90 percent of her clerks had more than one earlier clerkship.[17]Sarah Isgur, "The New Trend Keeping Women Out of the Country’s Top Legal Ranks," Politico, May 4, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/05/04/women-supreme-court-clerkships-485249.

The Court’s human resources manual specifies that employees are not allowed to reveal any confidential information that has not been made public by the Court. Law clerks, who are considered temporary employees, are also subject to the Supreme Court Law Clerk Code of Conduct, which states that clerks owe both justices and the Court itself “complete confidentiality, accuracy, and loyalty.”[18]Gail A. Curley, "Statement of the Court Concerning the Leak Investigation," https://legacy.amarkfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/dobbs-leak-report.pdf, January 19, 2023

Most former clerks opt to maintain that confidentiality even after their clerkship is finished, and therefore do not speak about discussions they observed or even the extent of the tasks they performed, such as whether they helped to draft opinions or made recommendations on accepting cases.[19]Artemus Ward and Todd C. Peppers (eds.), In Chambers: Stories of Supreme Court Law Clerks and Their Justices, University of Virginia Press, 2012

III. Demographics

Since the 1940s, just under half of all law clerks have come from Harvard and Yale, while many of the rest went to law school at the University of Chicago, Stanford, and Columbia. The sitting justices have hired a total 463 clerks through 2022, and 46 percent of those clerks went to Harvard or Yale.[20]Mark C. Miller, “Law Clerks and Their Influence at the US Supreme Court: Comments on Recent Works by Peppers and Ward,” Law & Social Inquiry, April 22, 2014, … Continue reading All of the sitting justices went to law school at Harvard or Yale, except for Amy Coney Barrett, who went to Notre Dame.[21]Supreme Court of the United States, “FAQs - Supreme Court Justices,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/faq_justices.aspx.

A 1998 analysis by USA Today of all the clerks that had been hired by the justices on the Court at that time found that they were "overwhelmingly white and male." Just 1.8 percent were Black, one percent Hispanic, and 4.5 percent Asian; one in four were female. Four of the nine justices at that time had never hired a Black clerk.[22]Tony Mauro, "From the Archives | the Hidden Power Behind the Supreme Court: Justices Give Pivotal Role to Novice Lawyers" USA Today, August 30, 2022, https://archive.ph/nkCI1#selection-541.0-541.107. Diversity among the clerks has increased slightly since then, but records show some classes are more diverse than others. David Lat, a legal writer, says there has been more gender parity in the last five terms. Kavanaugh made history in 2018 when he selected an all-female set of law clerks and tipped the scales towards the first majority-female clerk class ever.[23]Emily Baumgaertner, "Justice Kavanaugh’s Law Clerks Are All Women, a First for the Supreme Court," New York Times, October 18, 2022, … Continue reading The 2021 class of clerks was 51 percent male and 49 percent female, but the disparity returned in 2022.[24]David Lat, “Supreme Court Clerk Hiring Watch: Meet The October Term 2022 SCOTUS Clerks,” Original Jurisdiction, July 20, 2022, https://davidlat.substack.com/p/supreme-court-clerk-hiring-watch-ee0.

There are 38 law clerks for the 2022 term, 36 for the sitting justices and one each for retired justices Anthony Kennedy and Stephen Breyer. Of those clerks, 25 are men (66 percent) and 13 are women (34 percent). The Supreme Court does not release the race or ethnicity of clerks, so guesses are made based on information gleaned online. One expert estimates that 32 of the 38 clerks in 2022 are white (84 percent). All of the clerks went to one of ten law schools, mostly Yale (12), Harvard (8), and Stanford (7).[25]David Lat, “Supreme Court Clerk Hiring Watch: Meet The October Term 2022 SCOTUS Clerks,” Original Jurisdiction, July 20, 2022, https://davidlat.substack.com/p/supreme-court-clerk-hiring-watch-ee0.

The results of a January 2023 study by law professors at Vanderbilt University, University of Toronto and University of Virginia mirrored the clerk demographic data presented above.[26]Tracey E. George, Albert H. Yoon and Mitu Gulati, “Some Are More Equal Than Others: U.S. Supreme Court Clerkships,” SSRN, January 27, 2023, … Continue reading Examining a list of the 1,426 Supreme Court law clerks who clerked between 1980 and 2020, the researchers found that 69 percent of all clerks in that timeframe were male and 87 percent were white.

The authors calculated that 94% of clerks over those 40 years had attended a law school ranked in the top 25 by U.S. News and World Report, including 45 percent who went to Yale or Harvard. They also found that Harvard Law students who completed their undergraduate degrees at Harvard, Yale or Princeton were more likely to to be chosen as Supreme Court law clerks than their classmates with similar academic achievements who went to other undergraduate institutions.

The study was able to track the post-clerkship careers of 94% of clerks, finding that they had “high professional success after their clerkships, across a range of pursuits, within and outside of the law.” Many went on to be partners at top law firms, while others became venture capitalists, writers, academics, and even judges.

IV. Influence

A few months prior to the official ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Politico published a draft majority opinion that indicated the Court had voted to take away the right to legal abortion.[27]Josh Gerstein and Alexander Ward, “Supreme Court Has Voted to Overturn Abortion Rights, Draft Opinion Shows,” politico.com, May 2, 2022, … Continue reading That bombshell was soon overshadowed by the realization that an insider had taken the rare action of breaking the Court’s confidentiality agreement. The 36 law clerks working for the justices made up approximately half of the estimated 70 people who might have had access to draft opinions, putting them in the spotlight of the investigation to find the leak.[28]Jessica Gresko, “Court That Rarely Leaks Does So Now in Biggest Case in Years,” apnews.com, May 3, 2022, … Continue reading Coincidentally, the original Roe v. Wade decision in 1973 was leaked to a reporter by law clerk Larry Hammond with the understanding that it would only be published after the Court had officially released its opinion. The official ruling was unexpectedly delayed, and the scoop in TIME magazine hit the newsstands a couple of hours prior to the Court's announcement.[29]Rachel Treisman, “The Original Roe v. Wade Ruling Was Leaked, Too,” npr.org, May 3, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/05/03/1096097236/roe-wade-original-ruling-leak

Back in 1957, U.S. News and World Report asked whether “the influence of these young law clerks—some not yet admitted to the bar—is reflected in Court opinions.”[30]Todd C. Peppers, Courtiers of the Marble Palace, Stanford Law and Politics, 2006 With the attention on the role of Supreme Court law clerks following the 2022 leak, questions about how much influence they have over cases arose again. Any persuasive impact that clerks might have troubles some because the clerks are young, inexperienced lawyers who are not elected or confirmed to the position, and their identities are unknown to the general public.[31]Adam Bonica, Adam Chilton, Jacob Goldin, Kyle Rozema, and Maya Sen, “Legal Rasputins? Law Clerk Influence on Voting at the U.S. Supreme Court,” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, … Continue reading

Scholars say measuring their impact on the Supreme Court is difficult for two chief reasons. First, their ideological views are often aligned with the justices they serve and as such it can be "difficult to distinguish the effect of the clerk from the effect of the justice's own ideology."[32]Adam Bonica, Adam Chilton, Jacob Goldin, Kyle Rozema, and Maya Sen, “Legal Rasputins? Law Clerk Influence on Voting at the U.S. Supreme Court,” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, … Continue reading Second, it may not be known what outcome the clerks desired in each case, making it difficult to assess what influence they may have had over how a justice voted. One study looked at political donations made by clerks to analyze whether the clerks' political ideologies affected judicial voting behavior. The study found that "a justice would cast approximately 4% more conservative votes in a term when employing his or her most conservative clerks, when compared with a term in which the justice employs his or her most liberal clerks.” The influence of law clerks was stronger on cases in which the justices were evenly divided (12 percent), in high-profile cases (17 percent), and in legally significant cases (22 percent). The authors interpreted the results as suggesting that “clerk influence operates through clerks persuading their justice to follow the clerk’s preferred outcome.” However, they also said, "our findings suggest the influence of clerks is less troubling than one might otherwise believe."[33]Adam Bonica, Adam Chilton, Jacob Goldin, Kyle Rozema, and Maya Sen, “Legal Rasputins? Law Clerk Influence on Voting at the U.S. Supreme Court,” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, … Continue reading

A five-month investigation by USA Today in 1998 "found few signs of ideological manipulation by today's clerks," despite the fact that eight of the nine justices at the time routinely allowed clerks to write the first drafts of their opinions and used the cert pool to determine which cases would be heard. Even the ninth justice, John Paul Stevens, occasionally allowed clerks to draft opinions and review incoming cases, leading the article to report that "the vast majority" of cases submitted to the Court are turned down without ever being seen by a justice. Kenneth Starr, a former law clerk for Chief Justice Burger and the Whitewater independent counsel, criticized this practice in 1993, saying, "Selecting 100 or so cases from the pool of 6,000 petitions is just too important to invest in very smart but brand-new lawyers" and noting that "the court has ignored business cases that might seem boring to clerks, but crucial to commerce." Michael Dorf, a former clerk for Justice Kennedy and a constitutional law professor at Columbia University, told USA Today, "In the broad sweep of the law, the effect of clerks is negligible. But it is true that, sometimes, you will see lower courts deciding a case, basing a decision on their interpretation of a phrase that was written by a clerk."[34]Tony Mauro, "From the Archives | the Hidden Power Behind the Supreme Court: Justices Give Pivotal Role to Novice Lawyers," USA Today, August 30, 2022, https://archive.ph/nkCI1#selection-541.0-541.107.

The extent to which a law clerk's influence can be detected in Supreme Court opinions may depend on the justice's management style. A stylistic analysis of draft opinions by Lewis F. Powell, Jr., and Thurgood Marshall found less evidence of their clerks' fingerprints in the opinions of Powell, who had stricter procedures in place. The authors did find that "stylistic traces of the drafting clerks can be found in Powell’s and Marshall’s opinions." These findings, however, did not provide conclusive evidence that the clerks have undue influence. A former clerk reportedly said, "Even on those rare occasions when the clerk does the writing, the judge does the deciding."[35]Paul J. Wahlbeck, James F. Spriggs, II, and Lee Sigelman, "Ghostwriters on the Court?: A Stylistic Analysis of U.S. Supreme Court Opinion Drafts," American Politics Research, March 2002, … Continue reading In addition to draft opinions, researchers have looked for evidence of the clerks' impact on the choice of cases and voting decisions.[36]Christopher Kromphardt, "The Supreme Court Has More Clerks and Less Work Than 50 Years Ago," Washington Post, May 16, 2022, … Continue reading There does not appear to be a consensus on the extent of the influence that law clerks have on Supreme Court rulings.

V. Law Clerks for Sitting Justices

Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. (2005 to present)

Born on January 27, 1955, in Buffalo, New York, John G. Roberts, Jr is the 17th Chief Justice of the United States. Nominated by President George W. Bush to replace Chief Justice Rehnquist (after his death), Roberts was confirmed on September 29, 2005, by a 78-22 Senate vote.[37]The Whitehouse Archives of President George W. Bush, “Judicial Nominations: Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr.,” georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, … Continue reading[38]United States Senate, “Supreme Court Nominations, present - 1789, senate.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/nominations/Nominations.shtml[39]Oyez.org, “William H. Rehnquist,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/william_h_rehnquist

Holding an A.B. from Harvard College (1976) and a J.D. from Harvard Law School (1979), Roberts clerked for Judge Friendly of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit from 1979 until 1980, and for Associate Justice Rehnquist of the Supreme Court of the United States in 1980.[40]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

Other Roles Prior to Appointment to the Supreme Court:[41]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

- Special Assistant to the Attorney General, United States Department of Justice (1981–1982)

- Associate Counsel to President Ronald Reagan, White House Counsel’s Office (1982–1986)

- Principal Deputy Solicitor General, United States Department of Justice (1989–1993)

- Private practice in Washington, D.C. (1986–1989, 1993–2003)

- Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit (2003-2005)

Click to see a full list of Chief Justice Roberts's law clerks since 2005.

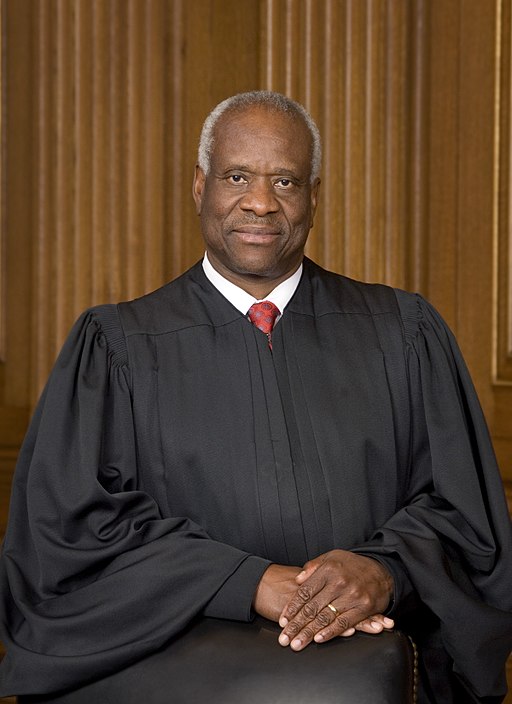

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas (1991 to present)

Born on June 23, 1948, in the Pinpoint Community near Savannah, Georgia, Clarence Thomas is the 111th confirmed Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Nominated by President George H. W. Bush to replace Associate Justice Marshall (after his retirement), he was confirmed on October 15, 1991 by a 52-48 Senate vote.[42]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [43]United States Senate, “Supreme Court Nominations, present - 1789, senate.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/nominations/Nominations.shtml [44]Oyez.org, “Thurgood Marshall,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/thurgood_marshall

Holding an A.B., cum laude, from the College of the Holy Cross (1971) and a J.D. from Yale Law School (1974), Thomas was admitted to the Missouri bar in 1974 where he served as Assistant Attorney General of Missouri from 1974 until 1977.[45]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

Other Roles Prior to Appointment to the Supreme Court:[46]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

- Attorney, Monsanto Company (1977-1979)

- Legislative Assistant to Senator John Danforth (1979-1981)

- Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, United States Department of Education (1981–1982)

- Chairman, United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (1982-1990)

- Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit (1990–1991)

Click to see a full list of Justice Thomas's law clerks since 1991.

Associate Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr. (2006 to present)

Born on April 1, 1950 in Trenton, New Jersey, Samuel A. Alito, Jr is the 115th confirmed Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Nominated by President George W. Bush to replace Associate Justice O’Connor (after her retirement), he was confirmed on January 31, 2006, by a 58-42 Senate vote.[47]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [48]United States Senate, “Supreme Court Nominations, present - 1789, senate.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/nominations/Nominations.shtml [49]Oyez.org, “Sandra Day O’Connor,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/sandra_day_oconnor

Holding an A.B. from Princeton University (1972) and a J.D. from Yale Law School (1975), Alito clerked for Judge Garth of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit from 1976 until 1977.[50]Aaron M. Houck, et al., “Samuel A. Alito, Jr.,” britannica.com, accessed November 2, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Samuel-A-Alito-Jr [51]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

Other Roles Prior to Appointment to the Supreme Court:[52]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

- Assistant United States Attorney, District of New Jersey (1977–1981)

- Assistant to the Solicitor General, United States Department of Justice (1981–1985)

- Deputy Assistant Attorney General, United States Department of Justice (1985–1987)

- United States Attorney, District of New Jersey (1987–1990)

- Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit (1990-2006)

Click to see a full list of Justice Alito's law clerks since 2006.

Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor (2009 to present)

Born on June 25, 1954, in the Bronx, New York, Sonia Sotomayor is the 116th confirmed Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Nominated by President Barack Obama to replace Associate Justice Souter (after his retirement), she was confirmed on August 6, 2009, by a 68-31 Senate vote.[53]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [54]United States Senate, “Supreme Court Nominations, present - 1789, senate.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/nominations/Nominations.shtml [55]Oyez.org, “David H. Souter,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/david_h_souter

Holding a B.A., summa cum laude, from Princeton University (1976) and a J.D. from Yale Law School (1979), Sotomayor was admitted to the New York bar in 1980 and served as Assistant District Attorney in the New York County District Attorney’s Office from 1979 until 1984.[56]Academy of Achievement, “Sonia Sotomayor,” achievement.org, February 9, 2022, https://achievement.org/achiever/sonia-sotomayor/ [57]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

Other Roles Prior to Appointment to the Supreme Court:[58]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

- Associate / Partner, Pavia & Harcourt, New York (1984–1992)

- Judge, United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (1992–1998)

- Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (1998–2009)

Click to see a full list of Justice Sotomayor's law clerks since 2009.

Associate Justice Elena Kagan (2010 to present)

Born on April 28, 1960, in New York City, New York, Elena Kagan is the 117th confirmed Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Nominated by President Barack Obama to replace Associate Justice Stevens (after his retirement), she was confirmed on August 5, 2010, by a 63-37 Senate vote.[59]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [60]United States Senate, “Supreme Court Nominations, present - 1789, senate.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/nominations/Nominations.shtml [61]Oyez.org, “John Paul Stevens,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/john_paul_stevens

Holding an A.B. from Princeton University (1981), an M.Phil. from Oxford University (1983) and a J.D. from Harvard Law School (1986), Kagan clerked for Judge Mikva of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit from 1986 to 1987 and for Associate Justice Marshall of the Supreme Court of the United States in 1987.[62]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

Other Roles Prior to Appointment to the Supreme Court:[63]Ballotpedia.org, “Elana Kagan,” ballotpedia.org, accessed November 2, 2022, https://ballotpedia.org/Elena_Kagan[64]Oyez.com, "Elena Kagan," oyez.com, accessed November 2, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/elena_kagan

- Associate, Williams and Connolly, Washington, D.C. (1989-1991)

- Professor of Law, University of Chicago Law School (1991-1997)

- Special Counsel, United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary (1993)

- Deputy Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy, Clinton Administration (1997-1999)

- Huston Professor of Law, Harvard University (1999-2003)

- Dean, Harvard Law School (2003-2009)

- Solicitor General of the United States (2009-2010)

Click to see a full list of Justice Kagan's law clerks since 2010.

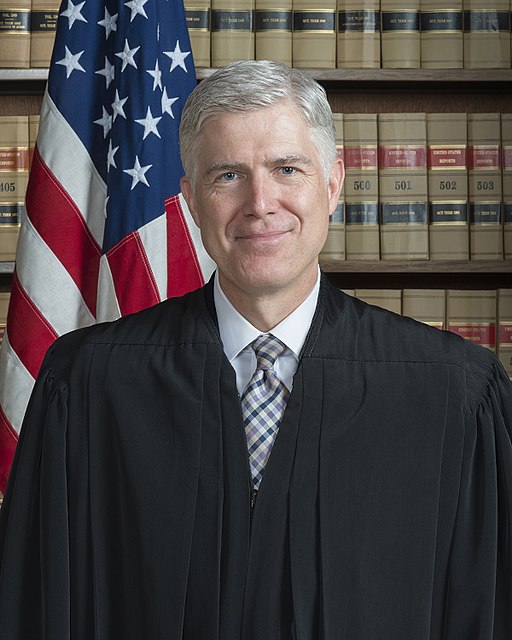

Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch (2017 to present)

Born on August 29, 1967, in Denver, Colorado, Neil M. Gorsuch is the 118th confirmed Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Nominated by President Donald Trump to replace Associate Justice Scalia (after his death), he was confirmed on April 7, 2017, by a 54-45 Senate vote.[65]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [66]United States Senate, “Supreme Court Nominations, present - 1789, senate.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/nominations/Nominations.shtml [67]Oyez.org, “Antonin Scalia,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/antonin_scalia

Holding a B.A. from Columbia University (1988) and a J.D. from Harvard Law School (1991), Gorsuch clerked for Judge Sentelle of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit from 1991 to 1992, and for Associate Justices White and Kennedy from 1993 to 1994. Gorsuch earned a D.Phil. from Oxford University in 2004.[68]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [69]Ballotpedia.org, “Neil Gorsuch,” ballotpedia.org, accessed November 2, 2022, https://ballotpedia.org/Neil_Gorsuch

Other Roles Prior to Appointment to the Supreme Court:[70]Ballotpedia.org, “Neil Gorsuch,” ballotpedia.org, accessed November 2, 2022, https://ballotpedia.org/Neil_Gorsuch [71]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

- Associate / Partner, Kellogg, Huber, Hansen, Todd, Evans, and Figel, Washington D.C. (1995-1998 / 1998-2005)

- Principal Deputy Associate Attorney General, United States Department of Justice (2005-2006)

- Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit (2006-2017)

Click to see a full list of Justice Gorsuch's law clerks since 2017.

Associate Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh (2018 to present)

Born on February 12, 1965, in Washington, D.C., Brett M. Kavanaugh is the 119th confirmed Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Nominated by President Donald Trump to replace Associate Justice Kennedy (after his retirement), he was confirmed on October 6, 2018, by a 50-48 Senate vote.[72]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [73]United States Senate, “Supreme Court Nominations, present - 1789, senate.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/nominations/Nominations.shtml [74]Oyez.org, “Anthony M. Kennedy,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/anthony_m_kennedy

Holding a B.A. from Yale College (1987) and a J.D. from Yale Law School (1990), Kavanaugh clerked for Judge Stapleton of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit from 1990 until 1991, Judge Kozinski of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit from 1991 until 1992, and for Associate Justice Kennedy of the Supreme Court of the United States in 1993.[75]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

Other Roles Prior to Appointment to the Supreme Court:[76]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [77]Ballotpedia.org, “Brett Kavanaugh,” ballotpedia.org, accessed November 2, 2022, https://ballotpedia.org/Brett_Kavanaugh

- Staff Attorney, Office of the Solicitor General of the United States (1992-1993)

- General Counsel, Judiciary Branch (1994-1997)

- Associate Counsel, Office of Independent Counsel (1998)

- Partner, private practice in Washington, D.C. (1997-1998, 1999-2001)

- Associate Counsel / Senior Associate Counsel to President George W. Bush (2001-2003)

- Assistant to the President and Staff Secretary for President George W. Bush (2003-2006)

- Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit (2006-2018)

Click to see a full list of Justice Kavanaugh's law clerks since 2018.

Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett (2020 to present)

Born on January 28, 1972, in New Orleans, Louisiana, Amy Coney Barrett is the 120th confirmed Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Nominated by President Donald Trump to replace Associate Justice Ginsburg (after her death), she was confirmed on October 26, 2020, by a 52-48 Senate vote.[78]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [79]United States Senate, “Roll Call Vote 116th Congress - 2nd Session, Vote Number 224,” senate.gov, October 26, 2020, … Continue reading[80]American Bar Association, “Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg Passes, Justice Amy Coney Barrett Seated as Replacement,” americanbar.org, January 25, 2021, … Continue reading

Holding a B.A. from Rhodes College (1994) and a J.D. from Notre Dame Law School (1997), Barrett clerked for Judge Silberman of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit from 1997 to 1998, and for Associate Justice Scalia of the Supreme Court of the United States in 1998.[81]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

Other Roles Prior to Appointment to the Supreme Court:[82]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [83]Ballotpedia.org, “Amy Coney Barret,” ballotpedia.org, accessed November 2, 2022, https://ballotpedia.org/Amy_Coney_Barrett

- Associate, Miller, Cassidy, Larroca & Lewin, Washington D.C. (1999-2000)

- Associate, Baker Botts LLP, Washington D.C. (2001)

- John M. Olin Fellow in Law, George Washington University School of Law (2001-2002)

- Professor of Law, Notre Dame Law School (2002-2017)

- Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, (2017-2020)

Click to see a full list of Justice Barrett's law clerks since 2020.

Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson (2022 to present)

Born on September 14, 1970, in Washington, D.C., Ketanji Brown Jackson is the 121st confirmed Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Nominated by President Joe Biden to replace Associate Justice Breyer (after his retirement), she was confirmed on April 7, 2022, by a 53-47 Senate vote.[84]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [85]United States Senate, “Roll Call Vote 117th Congress - 2nd Session, Vote Number 134,” senate.gov, https://www.senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_votes/vote1172/vote_117_2_00134.htm [86]Dan Mangan and Kevin Breuninger, “Ketanji Brown Jackson Sworn in as Supreme Court Justice, Replacing Steven Breyer,” cnbc.com, June 30, 2022, … Continue reading

Holding an A.B., magna cum laude, from Harvard-Radcliffe College (1992) and a J.D., cum laude, from Harvard Law School (1996), Jackson clerked for Judge Saris of the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts from 1996 to 1997, Judge Selya of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit from 1997 to 1998, and for Associate Justice Breyer of the Supreme Court of the United States in 1999.[87]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx

Other Roles Prior to Appointment to the Supreme Court:[88]Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [89]Ballotpedia.org, “Ketanji Brown Jackson,” ballotpedia.org, accessed November 2, 2022, https://ballotpedia.org/Ketanji_Brown_Jackson [90]Tamia Sutherland and Russ Bleemer, "Nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson's ADR Work," blog.cpradr.org, February 25, 2022, https://blog.cpradr.org/2022/02/25/nominee-ketanji-brown-jacksons-adr-work/

- Associate, Miller, Cassidy, Larroca & Lewin LLP, Washington, D.C. (1998-1999)

- Associate, Goodwin Procter LLP, Boston, Massachusetts (2000-2002)

- Associate, The Feinberg Group LLP, Washington D.C. (2002-2003)

- Assistant Special Counsel, United States Sentencing Commission (2003-2005)

- Assistant Federal Public Defender, Office of the Federal Public Defender (2005-2007)

- Of Counsel, Morrison & Foerster LLP, Washington D.C. (2007-2010)

- Vice Chair / Commissioner, United States Sentencing Commission (2010-2014)

- Judge, United States District Court for D.C. (2013-2021)

- Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit (2021-2022)

Click to see a full list of Justice Jackson's law clerks since 2022.

VI. Conclusion

In the wake of the Dobbs decision leak, the Court vowed to find out who released the draft opinion. "To the extent this betrayal of the confidences of the Court was intended to undermine the integrity of our operations, it will not succeed," said Chief Justice Roberts. "I have directed the Marshal of the Court to launch an investigation into the source of the leak."[91]Kevin Breuninger, "Supreme Court Says Leaked Abortion Draft Is Authentic; Roberts Orders Investigation Into Leak," CNBC, May 3, 2022, … Continue reading The turmoil initially threatened to eclipse the work of the Court as one source described the internal atmosphere as "imploding," and another saying, "I don't know how on earth the court is going to finish up its work this term."[92]Nina Totenberg, "After the Leak, the Supreme Court Seethes With Resentment and Fear Behind the Scenes," NPR, June 8, 2022, … Continue reading

The internal probe involved law clerks being asked to hand over their personal cell phone records and sign affidavits that could create a criminal liability if proven false. The media reported that some clerks may have consulted lawyers about those requests, and experts speculated that the mere act of retaining counsel could make the clerks appear guilty.[93]Tierney Sneed, "After the Leak, the Supreme Court Seethes With Resentment and Fear Behind the Scenes," CNN, June 1, 2022, … Continue reading

Although a new class of incoming clerks started in October 2022, the final Dobbs leak investigation report from Gail A. Curley, Marshal of the Supreme Court, was not released until January 19, 2023. Curley characterized the leak as "a grave assault on the judicial process." The Court was ultimately unable to identify the source of the leak "by a preponderance of the evidence," but found it unlikely that an outsider gained access through a technology breach.[94]Gail A. Curley, "Statement of the Court Concerning the Leak Investigation," https://legacy.amarkfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/dobbs-leak-report.pdf, January 19, 2023

The above analysis shows that law clerks for the Supreme Court are usually high-achieving students from top-tier law schools who have previously clerked for more than one lower court judge. Half of all clerks since the 1940s attended law school at Yale or Harvard, as did eight of the nine sitting justices.

Since law clerks were first selected in 1882, the majority have been white and male. In recent years, some justices have made an effort to hire more women and people of different races. The 2022-2023 class is composed of 25 men (66 percent) and 13 women (34 percent), and an estimated 32 of the 38 clerks are white (84 percent).

Many Supreme Court law clerks have gone on to hold positions of influence and command high salaries at prestige law firms. Six of the nine current justices are former Supreme Court law clerks.

Today's Supreme Court has six conservative and three liberal justices. In the 2021-2022 term, 29% of cases were decided unanimously, the lowest rate in the 20 years of records.[95]Angie Gou, Ellena Erskine, and James Romoser, "Stat Pack for the Supreme Court’s 2021-22 Term," SCOTUS Blog, July 1, 2022, … Continue reading In the 2022-2023 term, the Court will be taking on cases related to affirmative action, voting rights, and free speech. The fact that justices tend to select clerks with a similar political ideology to their own could mitigate whatever ideological impact clerks might otherwise have had. The use of clerks to vet cases and draft opinions, however, leaves room for the possibility that these young and relatively inexperienced clerks may have some impact on the workings of the Supreme Court.

Test your knowledge on this topic by taking our Supreme Court Quiz.

References

| ↑1, ↑28 | Jessica Gresko, “Court That Rarely Leaks Does So Now in Biggest Case in Years,” apnews.com, May 3, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/roe-wade-supreme-court-leaked-draft-opinion-c6a923f6e370672f4a5ccfd3be325786. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑5, ↑30 | Todd C. Peppers, Courtiers of the Marble Palace, Stanford Law and Politics, 2006 |

| ↑3 | Mark C. Miller, “Law Clerks and Their Influence at the US Supreme Court: Comments on Recent Works by Peppers and Ward,” Law & Social Inquiry, April 22, 2014, https://www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/r32761.pdf. |

| ↑4 | Supreme Court of the United States, “FAQs – Supreme Court Justices,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/faq_justices.aspx. |

| ↑6 | Roy Strom, “SCOTUS Clerks Have Everything to Lose as Leak Probe Launches,” Bloomberg Law, May 3, 2022, https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and-practice/scotus-clerks-have-everything-to-lose-as-leak-probe-launches. |

| ↑7 | Christopher Kromphardt, “The Supreme Court Has More Clerks and Less Work Than 50 Years Ago,” Washington Post, May 16, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/05/16/scotus-clerks-roe-dodd-clarence-thomas/. |

| ↑8 | Angie Gou, Ellena Erskine, and James Romoser, “Stat Pack for the Supreme Court’s 2021-22 term,” SCOTUS Blog, July 1, 2022, https://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/SCOTUSblog-Final-STAT-PACK-OT2021.pdf. |

| ↑9 | Supreme Court of the United States, “The Supreme Court at Work,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 17, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/courtatwork.aspx. |

| ↑10 | Public Information Office of the Supreme Court of the United States, “A Reporter’s Guide to Applications Pending Before the Supreme Court of the United States,” supremecourt.gov, September 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/publicinfo/reportersguide.pdf |

| ↑11, ↑20 | Mark C. Miller, “Law Clerks and Their Influence at the US Supreme Court: Comments on Recent Works by Peppers and Ward,” Law & Social Inquiry, April 22, 2014, https://www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/r32761.pdf. |

| ↑12 | Lawrence Baum, “Hiring Supreme Court Law Clerks: Probing the Ideology Between Judges and Justices,” Marquette Law Review, 2014, https://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5224&context=mulr. |

| ↑13 | Gil Seinfeld, “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Reflections of a Counterclerk,” Michigan Law Review First Impressions, 2016, https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1156&context=mlr_fi. |

| ↑14 | Adam Liptak, “A Sign of the Court’s Polarization: Choice of Clerks,” nytimes.com, September 6, 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/07/us/politics/07clerks.html. |

| ↑15 | United States Courts, “Supreme Court Procedures,” uscourts.gov, accessed November 3, 2022, https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/educational-resources/about-educational-outreach/activity-resources/supreme-1. |

| ↑16, ↑31, ↑32, ↑33 | Adam Bonica, Adam Chilton, Jacob Goldin, Kyle Rozema, and Maya Sen, “Legal Rasputins? Law Clerk Influence on Voting at the U.S. Supreme Court,” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, March 2019, https://oconnell.fas.harvard.edu/files/msen/files/clerk-influence.pdf. |

| ↑17 | Sarah Isgur, "The New Trend Keeping Women Out of the Country’s Top Legal Ranks," Politico, May 4, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/05/04/women-supreme-court-clerkships-485249. |

| ↑18, ↑94 | Gail A. Curley, "Statement of the Court Concerning the Leak Investigation," https://legacy.amarkfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/dobbs-leak-report.pdf, January 19, 2023 |

| ↑19 | Artemus Ward and Todd C. Peppers (eds.), In Chambers: Stories of Supreme Court Law Clerks and Their Justices, University of Virginia Press, 2012 |

| ↑21 | Supreme Court of the United States, “FAQs - Supreme Court Justices,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/faq_justices.aspx. |

| ↑22 | Tony Mauro, "From the Archives | the Hidden Power Behind the Supreme Court: Justices Give Pivotal Role to Novice Lawyers" USA Today, August 30, 2022, https://archive.ph/nkCI1#selection-541.0-541.107. |

| ↑23 | Emily Baumgaertner, "Justice Kavanaugh’s Law Clerks Are All Women, a First for the Supreme Court," New York Times, October 18, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/09/us/politics/kavanaugh-women-law-clerks.html. |

| ↑24, ↑25 | David Lat, “Supreme Court Clerk Hiring Watch: Meet The October Term 2022 SCOTUS Clerks,” Original Jurisdiction, July 20, 2022, https://davidlat.substack.com/p/supreme-court-clerk-hiring-watch-ee0. |

| ↑26 | Tracey E. George, Albert H. Yoon and Mitu Gulati, “Some Are More Equal Than Others: U.S. Supreme Court Clerkships,” SSRN, January 27, 2023, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4338222 |

| ↑27 | Josh Gerstein and Alexander Ward, “Supreme Court Has Voted to Overturn Abortion Rights, Draft Opinion Shows,” politico.com, May 2, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/05/02/supreme-court-abortion-draft-opinion-00029473 |

| ↑29 | Rachel Treisman, “The Original Roe v. Wade Ruling Was Leaked, Too,” npr.org, May 3, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/05/03/1096097236/roe-wade-original-ruling-leak |

| ↑34 | Tony Mauro, "From the Archives | the Hidden Power Behind the Supreme Court: Justices Give Pivotal Role to Novice Lawyers," USA Today, August 30, 2022, https://archive.ph/nkCI1#selection-541.0-541.107. |

| ↑35 | Paul J. Wahlbeck, James F. Spriggs, II, and Lee Sigelman, "Ghostwriters on the Court?: A Stylistic Analysis of U.S. Supreme Court Opinion Drafts," American Politics Research, March 2002, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1532673X02030002003. |

| ↑36 | Christopher Kromphardt, "The Supreme Court Has More Clerks and Less Work Than 50 Years Ago," Washington Post, May 16, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/05/16/scotus-clerks-roe-dodd-clarence-thomas/. |

| ↑37 | The Whitehouse Archives of President George W. Bush, “Judicial Nominations: Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr.,” georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/judicialnominees/roberts.html |

| ↑38 | United States Senate, “Supreme Court Nominations, present - 1789, senate.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/nominations/Nominations.shtml |

| ↑39 | Oyez.org, “William H. Rehnquist,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/william_h_rehnquist |

| ↑40, ↑41, ↑42, ↑45, ↑46, ↑47, ↑52, ↑53, ↑57, ↑58, ↑59, ↑62, ↑65, ↑68, ↑71, ↑72, ↑75, ↑76, ↑78, ↑81, ↑82, ↑84, ↑87, ↑88 | Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx |

| ↑43 | United States Senate, “Supreme Court Nominations, present - 1789, senate.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/nominations/Nominations.shtml |

| ↑44 | Oyez.org, “Thurgood Marshall,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/thurgood_marshall |

| ↑48, ↑54, ↑60, ↑66, ↑73 | United States Senate, “Supreme Court Nominations, present - 1789, senate.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/nominations/Nominations.shtml |

| ↑49 | Oyez.org, “Sandra Day O’Connor,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/sandra_day_oconnor |

| ↑50 | Aaron M. Houck, et al., “Samuel A. Alito, Jr.,” britannica.com, accessed November 2, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Samuel-A-Alito-Jr |

| ↑51 | Supreme Court of the United States, “Current Members,” supremecourt.gov, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx |

| ↑55 | Oyez.org, “David H. Souter,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/david_h_souter |

| ↑56 | Academy of Achievement, “Sonia Sotomayor,” achievement.org, February 9, 2022, https://achievement.org/achiever/sonia-sotomayor/ |

| ↑61 | Oyez.org, “John Paul Stevens,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/john_paul_stevens |

| ↑63 | Ballotpedia.org, “Elana Kagan,” ballotpedia.org, accessed November 2, 2022, https://ballotpedia.org/Elena_Kagan |

| ↑64 | Oyez.com, "Elena Kagan," oyez.com, accessed November 2, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/elena_kagan |

| ↑67 | Oyez.org, “Antonin Scalia,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/antonin_scalia |

| ↑69, ↑70 | Ballotpedia.org, “Neil Gorsuch,” ballotpedia.org, accessed November 2, 2022, https://ballotpedia.org/Neil_Gorsuch |

| ↑74 | Oyez.org, “Anthony M. Kennedy,” oyez.org, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.oyez.org/justices/anthony_m_kennedy |

| ↑77 | Ballotpedia.org, “Brett Kavanaugh,” ballotpedia.org, accessed November 2, 2022, https://ballotpedia.org/Brett_Kavanaugh |

| ↑79 | United States Senate, “Roll Call Vote 116th Congress - 2nd Session, Vote Number 224,” senate.gov, October 26, 2020, https://www.senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_votes/vote1162/vote_116_2_00224.htm |

| ↑80 | American Bar Association, “Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg Passes, Justice Amy Coney Barrett Seated as Replacement,” americanbar.org, January 25, 2021, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/committees/death_penalty_representation/project_press/2020/year-end-2020/amy-coney-barrett-replaces-ginsburg-on-supreme-court/ |

| ↑83 | Ballotpedia.org, “Amy Coney Barret,” ballotpedia.org, accessed November 2, 2022, https://ballotpedia.org/Amy_Coney_Barrett |

| ↑85 | United States Senate, “Roll Call Vote 117th Congress - 2nd Session, Vote Number 134,” senate.gov, https://www.senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_votes/vote1172/vote_117_2_00134.htm |

| ↑86 | Dan Mangan and Kevin Breuninger, “Ketanji Brown Jackson Sworn in as Supreme Court Justice, Replacing Steven Breyer,” cnbc.com, June 30, 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/06/30/supreme-court-justice-ketanji-brown-jackson-sworn-in-replaces-breyer.html |

| ↑89 | Ballotpedia.org, “Ketanji Brown Jackson,” ballotpedia.org, accessed November 2, 2022, https://ballotpedia.org/Ketanji_Brown_Jackson |

| ↑90 | Tamia Sutherland and Russ Bleemer, "Nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson's ADR Work," blog.cpradr.org, February 25, 2022, https://blog.cpradr.org/2022/02/25/nominee-ketanji-brown-jacksons-adr-work/ |

| ↑91 | Kevin Breuninger, "Supreme Court Says Leaked Abortion Draft Is Authentic; Roberts Orders Investigation Into Leak," CNBC, May 3, 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/05/03/supreme-court-says-leaked-abortion-draft-is-authentic-roberts-orders-investigation-into-leak.html. |

| ↑92 | Nina Totenberg, "After the Leak, the Supreme Court Seethes With Resentment and Fear Behind the Scenes," NPR, June 8, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/06/08/1103476028/after-the-leak-the-supreme-court-seethes-with-resentment-and-fear-behind-the-sce. |

| ↑93 | Tierney Sneed, "After the Leak, the Supreme Court Seethes With Resentment and Fear Behind the Scenes," CNN, June 1, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/06/01/politics/supreme-court-clerks-leak-investigation-phones-affidavit-abortion/index.html. |

| ↑95 | Angie Gou, Ellena Erskine, and James Romoser, "Stat Pack for the Supreme Court’s 2021-22 Term," SCOTUS Blog, July 1, 2022, https://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/SCOTUSblog-Final-STAT-PACK-OT2021.pdf. |