Last updated July 18, 2023 | Take the Quiz

Quick Facts:

- An estimated 90% of fentanyl in the United States comes from Mexico. Transnational crime organizations (TCOs) in Mexico use the money from drug sales to buy more guns to defend their operations, creating a cycle often referred to as a drugs-to-guns pipeline.

- Mexico’s restrictive gun laws make it difficult for TCOs to acquire firearms legally in Mexico, but they are able to acquire weapons in the U.S. An estimated 200,000-873,000 firearms are smuggled into Mexico annually, and 70-90% of guns recovered at crime scenes in Mexico can be traced back to the U.S.

- The U.S. government deemed the trafficking of firearms into Mexico a national security threat because those guns facilitate the illegal drug trade, which has contributed to increasing rates of American drug overdose deaths.

- Via the Mérida Initiative, which Mexico labeled a failure, the U.S. spent $3.5 billion from FY 2008 to FY 2021 to modernize the Mexican Army, combat TCOs and disrupt the pipeline of northbound drugs.

- In 2021, the Mexican government filed a $10 billion civil suit against gun manufacturers in the U.S., stating that they “facilitate and encourage … purchasers who foreseeably traffic the guns into Mexico.”

- TCOs prefer assault weapons, especially .50 caliber weapons capable of piercing military armor. No U.S. federal or state laws in the four border states ban these weapons completely.

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary

II. Drugs Flow from Mexico into the U.S.

III. Gun Laws in the U.S. and Mexico

IV. Gun Flow into Mexico from the United States

V. U.S.-Mexico Efforts to Combat TCOs in the 21st Century

VI. Conclusion

I. Executive Summary

The shared border between the United States (U.S.) and Mexico runs nearly 2,000 miles long, creating the need for cooperation among the two countries to address violence and crime that spills across the border in both directions.

One driver of crime and violence is known as the drugs-to-guns pipeline. Guns and ammunition trafficked into Mexico from the U.S. are used by transnational crime organizations (TCOs) to protect their drug transportation hubs and routes along the U.S. southwest border and to defend plantation and manufacturing sites across Mexico. The firepower in the hands of TCOs makes it harder for Mexican and U.S. authorities to combat criminal activity, resulting in an increased flow of drugs into the U.S. and creating a vicious cycle of drugs-guns-drugs transactions.

Many of the drugs moving into the U.S. come from Mexico, including 90% of the deadly fentanyl, fueling a crisis of opioid overdose deaths. In Mexico, an estimated 70-90% of guns found at crime scenes are traced back to the U.S.

While the U.S. and Mexico are two of only three countries that have a constitutional right to bear arms, the gun laws in Mexico are far more restrictive. As a result, criminals acquire guns in the U.S. and move them into Mexico using the same transportation methods employed to move drugs north across the border. Decades of U.S.-Mexico joint efforts failed to disrupt the TCOs’ drug pipeline and the TCOs have emerged stronger and more powerful, armed with weapons sourced from the U.S.

II. Drugs Flow from Mexico into the U.S.

Mexican transnational crime organizations (TCOs) have well-established pipelines to move drugs from Mexico to the final consumer in the U.S. The DEA’s 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment report stated, “Mexican TCOs are the greatest drug trafficking threat to the United States; they control most of the U.S. drug market and have established varied transportation routes, have advanced communications capabilities, and hold strong affiliations with criminal groups and gangs in the United States.” [1]Drug Enforcement Administration, “National Drug Threat Assessment,” justice.gov, March 2021, https://www.justice.gov/usao-mdpa/page/file/1425276/download

Drug trafficking feeds addiction and drug abuse in the U.S., and the DEA attributes most of the cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin and fentanyl in the country to Mexican TCOs, who make these drugs readily available nationwide. [2]Drug Enforcement Administration, “National Drug Threat Assessment,” justice.gov, March 2021, https://www.justice.gov/usao-mdpa/page/file/1425276/download

Historically, Mexican-based TCOs controlled the cultivation and importation of marijuana and heroin into the U.S., while Colombian cartels controlled cocaine. Over time, Mexican TCOs took over the transportation and distribution of Colombian cocaine: by the early 2000s, 66% of Columbian cocaine entered the U.S. via Mexico. [3]United States Government Accountability Office, “Drug Control: U.S. Assistance Has Helped Mexican Counternarcotics Efforts, but Tons of Illicit Drugs Continue to Flow into the United States,” … Continue reading Shipments of fentanyl and the precursor chemicals used to manufacture it are sent from China and enter North America mostly through Mexico, allowing TCOs to expand their domination of the illegal opioid market. [4]Wilson Center Mexico Institute, “Mexico’s Role in the Deadly Rise of Fentanyl,” wilsoncenter.org, February 2019, … Continue reading

A 2022 report from Rand Corporation and the U.S. government stated that Mexico is now the “principal source” of illicit fentanyl in the U.S., whereas prior to 2019, as much as 80% of the supply was attributed to China.[5]Commission on Combating Synthetic Opioid Trafficking, “Final Report,” rand.org, February 8, 2022, https://www.rand.org/pubs/external_publications/EP68838.html Bipartisan legislation introduced by U.S. senators in 2023 stated that 90% of fentanyl in the U.S. came across the southern border, and declared that Mexican cartels trafficking fentanyl into the country constitutes a national security threat. [6]Tim Kaine, “Ernst, Kaine, Bice, Carbajal Introduce Bill to Combat Threat of Fentanyl,” kaine.senate.gov, May 16, 2023, … Continue reading

Experts believe that abuse of prescription opioids set the stage for the current fentanyl crisis in the U.S. [7]Brian Mann, “DEA moves to revoke major drug distributor’s license over opioid crisis failures,” NPR.org, May 26, 2023Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 100 times stronger than morphine and 50 times stronger than heroin, has flooded into the U.S. to devastating effect.[8]United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), “Fentanyl,” dea.gov, accessed May 29, 2023, https://www.dea.gov/factsheets/fentanyl Opioids, namely fentanyl, are the major cause of drug-related overdose deaths in the U.S., which have nearly quadrupled in the last decade. [9]Claire Klobucista and Alejandra Martinez, “Fentanyl and the U.S. Opioid Epidemic,” cfr.org, April 19, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/fentanyl-and-us-opioid-epidemic

Nearly 200 Americans died every day from fentanyl overdoses in 2021, a rate 25% higher than in 2020 and almost double the rate in 2019.[10]USA Facts, “Are Fentanyl Overdose Deaths Rising in the US?,” usafacts.org, December 9, 2022, https://usafacts.org/articles/are-fentanyl-overdose-deaths-rising-in-the-us/ Per the CDC, between 1999 and 2020, more than 564,000 people died from overdoses involving opioids.[11]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Understanding the Opioid Overdose Epidemic,” cdc.gov, last reviewed June 1, 2022, Why Can’t the U.S. and Mexico Annual drug overdose deaths in the U.S. surpassed 100,000 in 2021, at which point opioids were taking more American lives each year than firearms, motor vehicle crashes, suicides and homicides.[12] Kaitlin Sullivan and Reynolds Lewis, “’A Staggering Increase’: Yearly Overdose Deaths Top 100,000 for First Time,” nbcnews.com, November 17, 2021, … Continue reading [13]Commission on Combating Synthetic Opioid Trafficking, “Final Report,” rand.org, February 8, 2022, https://www.rand.org/pubs/external_publications/EP68838.html

Synthetic opioids differ from plant-based opioids in that they are easier to transport, more addictive, and cheaper and faster to produce. Manufacturing heroin requires a lot of land and time to grow the opium poppies. Fentanyl, by contrast, is synthesized from chemicals and thus requires far fewer resources, giving it higher profit margins.[14]Audrey Travère and Jules Giraudat, “Revealed: How Mexico's Sinaloa Cartel Has Created a Global Network to Rule the Fentanyl Trade,” theguardian.com, December 8, 2020, … Continue reading [15]Commission on Combating Synthetic Opioid Trafficking, “Final Report,” rand.org, February 8, 2022, https://www.rand.org/pubs/external_publications/EP68838.html A DEA official noted in a 2017 public hearing that one kilogram of fentanyl purchased from China for $3,000-5,000 could generate between $6.6 million and $10 million in revenue.[16]Joseph J. Schleigh, “Statement of Joseph J. Schleigh, Acting Section Chief Synthetic Drugs and Chemicals Section Diversion Control Division Drug Enforcement Administration,” ussc.gov, December 5, … Continue reading

Anne Milgram, Administrator of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, told the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in February 2023 that the Mexican Sinaloa and Jalisco cartels “pose the greatest criminal drug threat the United States has ever faced.” According to Milgram:

“The Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco Cartel and their affiliates control the vast majority of the fentanyl global supply chain, from manufacture to distribution. The cartels are buying precursor chemicals in the People’s Republic of China (PRC); transporting the precursor chemicals from the PRC to Mexico; using the precursor chemicals to mass produce fentanyl; pressing the fentanyl into fake prescription pills; and using cars, trucks, and other routes to transport the drugs from Mexico into the United States for distribution. It costs the cartels as little as 10 cents to produce a fentanyl-laced fake prescription pill that is sold in the United States for $10 to $30 per pill.”[17]Anne Milgram, “Countering Illicit Fentanyl Trafficking,” Senate Committee on Foreign Relations hearing, February 15, 2023, … Continue reading

The lucrative trade enabled by selling fentanyl provides TCOs with the financial means to amass firearms, upgrade anti-detection technology and expand operations. The TCOs have consolidated distribution networks within the U.S. with the help of U.S.-based Mexican gangs to create a seamless pipeline for moving products.[18]National Drug Intelligence Center, “National Drug Threat Assessment 2009: Drug Trafficking Organizations,” justice.gov, December 2008, … Continue reading

Today, the Mexican TCOs have a global network similar to that of a large corporation, using their existing networks to expand cross-border operations to include human trafficking from Mexico into the U.S. as well as gun trafficking and money laundering from the U.S. into Mexico. [19]National Drug Intelligence Center, “National Drug Threat Assessment 2009: Drug Trafficking Organizations,” justice.gov, December 2008, … Continue reading

The drug trade is marked by extreme violence, which inextricably links the production and movement of drugs with the guns needed to protect that industry. Ioan Grillo, author of Blood Gun Money: How America Arms Gangs and Cartels, wrote, “The illegal narcotics trade is huge, worth an estimated $150 billion a year in the United States alone… The gun black market claims a fraction of that worth but provides a tool that allows gangsters to control those drug profits.” [20] Ioan Grillo, “Blood Gun Money: How America Arms Gangs and Cartels,” Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021

While the violence in the U.S. is often associated with local drug sales and other criminal activity as a means to resolve disputes and maintain discipline, Congressional Research Service notes that the violence in Mexico has also "been dramatically punctuated by beheadings, public hangings of corpses, and murders of dozens of journalists and officials.”[21]June S. Beittel, “Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations,” crsreports.congress.gov, July 28, 2020, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R41576/45 A ranking of the 50 most violent cities in the world found that the top five were in Mexico. [22] June S. Beittel, “Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations,” crsreports.congress.gov, July 28, 2020, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R41576/45

III. Gun Laws in the U.S. and Mexico

The United States and Mexico are two of just three countries worldwide that have a constitutional right to bear arms. However, gun rights in Mexico are restrictive and heavily regulated in comparison to the U.S.[23] Brennan Weiss, James Pasley, and Azmi Haroun, “Only 3 Countries in the World Protect the Right to Bear Arms in Their Constitutions: The US, Mexico, and Guatemala,” businessinsider.com, … Continue reading[24]The third country is Guatemala. Ty McCormick, “How Many Countries Have Gun Rights Enshrined in Their Constitutions?,” foreignpolicy.com, April 5, 2013, … Continue reading Article 10 of the Mexican Constitution states: “The inhabitants of the United Mexican States have a right to arms in their homes, for security and legitimate defense, with the exception of arms prohibited by federal law and those reserved for the exclusive use of the Army, Navy, Air Force, and National Guard. Federal law will determine the cases, conditions, requirements, and places in which the carrying of arms will be authorized to the inhabitants.”[25] The original wording stated “are entitled to have arms of any kind in their possession,” but was altered when the constitution was revised in 1917. After this change, the right to bear arms … Continue reading

The second amendment of the U.S. Constitution, by contrast, does not mention restrictions: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” [26]National Constitution Center, “The United States Constitution,” constitutioncenter.org, accessed May 25, 2023, https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/full-text Although U.S. gun laws are less restrictive, the right to bear arms is not without some limits, such as background checks and prohibitions on the sale of guns to people under age 18 and possession by convicted felons.[27]Jonathan Masters, “How Do US Gun Laws Compare to Other Countries?,” pbs.org, November 17, 2017, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/how-do-u-s-gun-laws-compare-to-other-countries

Mexican gun laws and regulatory authority fall under the federal government’s administrative control, establishing one unified set of laws across the entire country.[28] Philip Alpers and Miles Lovell, “Mexico — Gun Facts, Figures and the Law,” gunpolicy.org, December 7, 2022, https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/region/mexico The U.S. has some federal gun laws that apply to everyone, but state gun laws vary widely across the country.[29] FindLaw, “Gun Laws,” findlaw.com, December 27, 2022, https://www.findlaw.com/injury/product-liability/gun-laws.html

There is only one gun and ammunition store in all of Mexico, which is on an army base and run by the Mexican military.[30] Many sources state that Mexico has only one gun store, but there may be a satellite store also run by the military serving just three states in the northeast of the country, known as O.T.C.A. … Continue reading [31] Wilma Gandoy Vázquez and Ximena García Hidalgo, “Mexico’s Bold Move Against Gun Companies,” Arms Control Association, September 2022, … Continue reading The process for buying a gun in Mexico entails obtaining a letter from local authorities to prove a lack of a criminal record, then submitting a letter proving employment status and income. Applicants must pass a background check, then travel to Mexico City to visit the only authorized gun store in the country. After being fingerprinted, the person may then buy a gun.[32] Audrey Carlsen and Sahil Chinoy, “How to Buy a Gun in 16 Countries,” nytimes.com, August 6, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/03/02/world/international-gun-laws.html Receiving government approval to purchase a gun can take months.[33] Ioan Grillo, “Blood Gun Money: How America Arms Gangs and Cartels,” Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021 Guns are registered with the government, and people who want to carry a firearm for protection must demonstrate the need.[34] MexLaw, “Some Basic Facts About Gun Control in Mexico,” mexlaw.com, accessed May 25, 2023, https://mexlaw.com/some-basic-facts-about-gun-control-in-mexico-2/ Hunters and sport shooters must belong to a shooting club through which their purchase requests are submitted.[35] Armas MX, “¿Como Adquirir un arma en México?,” armasmx.com, accessed May 25, 2023, https://www.armasmx.com/compra-de-armas

In the U.S., there are nearly 58,000 federally licensed firearms dealers and pawnbrokers.[36] United States Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, “Report of Active Firearms Licenses - License Type by State Statistics,” atf.gov, April 10, 2023, … Continue reading The basic buying process involves passing an instant background check and being over 18 years old or 21 years old, depending on the type of gun, although some states have added restrictions such as a waiting period and more extensive background checks.[37] Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, “Brady Law,” atf.gov, July 2021, https://www.atf.gov/rules-and-regulations/brady-law [38] Audrey Carlsen and Sahil Chinoy, “How to Buy a Gun in 16 Countries,” nytimes.com, August 6, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/03/02/world/international-gun-laws.html [39] Giffords, “Universal Background Checks,” giffords.org, accessed May 29, 2023, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/gun-laws/policy-areas/background-checks/universal-background-checks/

There are loopholes to avoid background checks in many states, such as private or secondhand sales (as opposed to purchasing from a licensed dealer) and transfers of guns in the form of a gift.[40] Rand Corporation, “The Effects of Background Checks,” rand.org, January 10, 2023, https://www.rand.org/research/gun-policy/analysis/background-checks.html Researchers from Northeastern University and Harvard University estimated that 26% of gun owners who purchased via private sale in states that regulated private firearms sales made the purchase without undergoing a background check. That number jumped to 57% in states that did not regulate private sales. Overall, 22% of gun owners reported that they did not undergo a background check in their most recent firearm purchase.[41] Matthew Miller, Lisa Hepburn and Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Acquisition Without Background Checks,” Annals of Internal Medicine, February 21, 2017, … Continue reading

As of May 2023, there was no federal ban on the purchase of assault weapons in the U.S.,[42] Joseph Stepansky, "U S Lawmakers Banned Assault Weapons in 1994. Why Can't They Now?" aljazeera.com, April 20, 2023, … Continue reading nor are there in three of the four border states (Arizona, New Mexico and Texas).[43] Giffords Law Center, "Assault Weapons in Arizona," giffords.org, last updated January 3, 2023, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/state-laws/assault-weapons-in-arizona/ [44] Giffords Law Center, "Assault Weapons in New Mexico," giffords.org, last updated January 5, 2023, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/state-laws/assault-weapons-in-new-mexico/ [45] Giffords Law Center, "Assault Weapons in Texas," giffords.org, last updated January 3, 2023, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/state-laws/assault-weapons-in-texas/ In California, assault weapons can only be sold to a licensed gun dealer, police or sheriff's department or the holder of a special weapons permit issued by the Department of Justice. [46] Giffords Law Center, "Assault Weapons in California," giffords.org, last updated January 3, 2023, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/state-laws/assault-weapons-in-california/

IV. Gun Flow into Mexico from the United States

The history of firearms moving from the U.S. into Mexico dates back to Mexico’s War of Independence against Spain, starting in 1810.[47] New World Encyclopedia, “Mexican War of Independence,” newworldencyclopedia.org (accessed June 2, 2023), https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Mexican_War_of_Independence

While Mexico’s current restrictive gun laws make it difficult to acquire firearms legally in Mexico, TCOs need firepower to protect their drug profits. [48] Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking: US Efforts to Disrupt Gun Smuggling into Mexico Would Benefit from Additional Data and Analysis,” gao.gov, February 2021, … Continue reading To get around the country’s restrictions, an estimated 200,000-873,000 U.S. firearms are smuggled into the country each year.[49] Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking: US Efforts to Disrupt Gun Smuggling into Mexico Would Benefit from Additional Data and Analysis,” gao.gov, February 2021, … Continue reading [50] Conor Finnegan, “Gun used in kidnapping, killing of Americans in Mexico came from US,” abcnews.go.com, March 21, 2023, … Continue reading Between 70% and 90% of guns found at crime scenes in Mexico came from the U.S. This influx of weapons fuels violence and crime in Mexico. [51] Liz Mineo, “Stopping Toxic Flow of Guns from U.S. to Mexico,” news.harvard.edu, February 18, 2022, … Continue reading

In 2020, the U.S. Southwest Border Counternarcotics Strategy “identified the trafficking of firearms from the U.S. into Mexico as a threat to the safety and security of both countries” [52] Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking: US Efforts to Disrupt Gun Smuggling into Mexico Would Benefit from Additional Data and Analysis,” gao.gov, February 2021, … Continue reading because gun trafficking facilitates the illegal drug trade that endangers the lives of U.S. citizens.[53] Donald Trump, “Enforcing Federal Law with Respect to Transnational Criminal Organizations and Preventing International Trafficking,” federalregister.gov, February 9, 2017, … Continue reading

TCOs purchase guns in the U.S. using the proceeds from drug sales in the U.S. and move them into Mexico, leveraging the same pipeline of distribution networks and routes used to traffic drugs into the U.S.[54] Chris McGreal, “How Mexico's Drug Cartels Profit from Flow of Guns Across the Border,” theguardian.com, December 8, 2011, … Continue reading The United States Government Accountability Office reported that TCOs prefer .50 caliber rifles “because these rifles are powerful enough to disable a vehicle engine and penetrate vehicle or personal armor, posing a significant threat to Mexican security forces.” [55] Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking: US Efforts to Disrupt Gun Smuggling into Mexico Would Benefit from Additional Data and Analysis,” gao.gov, February 2021, … Continue reading

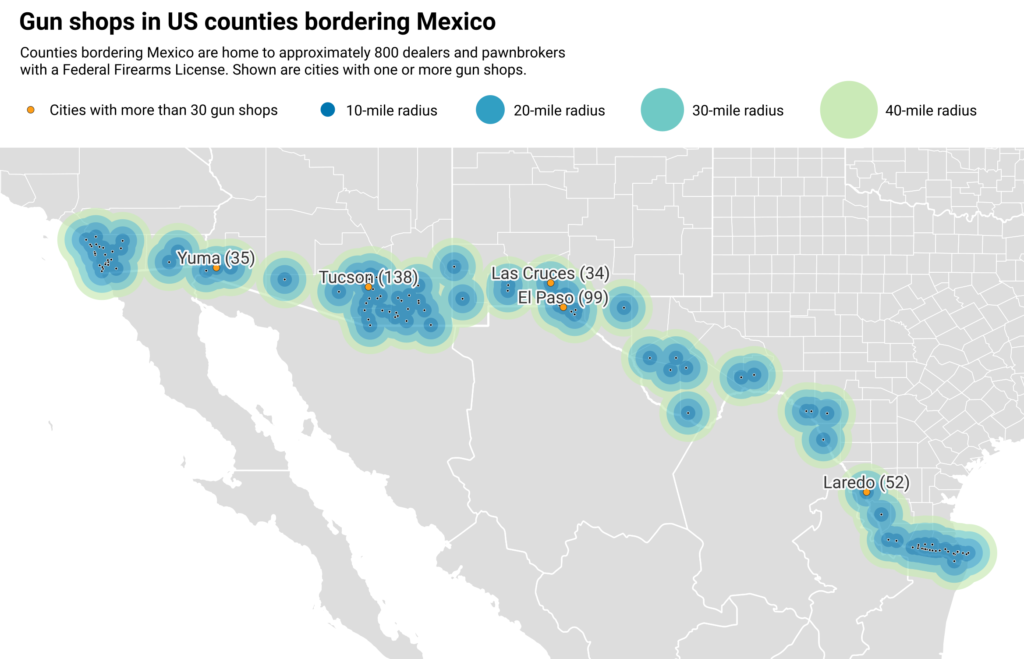

A 2013 University of San Diego study found that 46.7% of U.S. firearms dealers relied on TCOs’ demand for firearms to stay in business. [56] Topher McDougal, et al., "The Way of the Gun: Estimating Firearms Traffic Across the U.S.-Mexico Border," IGARAPE Institute, University of San Diego Trans-Border Institute, March 2023, … Continue reading In 2016, data from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) showed over 730 licensed firearm dealers in U.S. counties along the border with Mexico.[57] Christopher Ingraham, “Why Mexico’s Drug Cartels Love America’s Gun Laws,” washingtonpost.com, January 14, 2016, … Continue reading In May 2023, there were 9,534 gun dealers and pawnbrokers with federal firearms licenses in the four states along the southern border, including approximately 800 dealers and pawnbrokers in U.S. counties that border Mexico.[58] United States Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, “Report of Active Firearms Licenses - License Type by State Statistics,” atf.gov, May 10, 2023, … Continue reading

Map created in July 2023 using data from the ATF's Complete Federal Firearms Listings.

Mexican authorities argue that gun manufacturers and firearms dealers in the U.S. are not only aware of the huge demand for guns in Mexico but are also major beneficiaries of that demand, to the tune of an estimated $250 million annually.[59] Al Jazeera, “US Judge Dismisses Mexico’s $10bn Lawsuit Against Gun Makers,” aljazeera,com, October 1, 2022, … Continue reading [60]United States of Mexico, “Estados Unidos Mexicanos v. Smith & Wesson Brands, Inc.; Barrett Firearms Manufacturing, Inc.; Beretta U.S.A. Corp., et al.,” August 4, 2021 In 2021, the Mexican government filed a $10 billion civil lawsuit against several gun manufacturers in U.S. courts, stating that these companies “facilitate and encourage easy access by persons intent on murder, mayhem, or other crimes, including illegal purchasers who foreseeably traffic the guns into Mexico.” [61]United States of Mexico, “Estados Unidos Mexicanos v. Smith & Wesson Brands, Inc.; Barrett Firearms Manufacturing, Inc.; Beretta U.S.A. Corp., et al.,” August 4, 2021 The lawsuit was dismissed due to U.S. legal protections for gun manufacturers, but Mexico has appealed.[62] AP News, “US Judge Dismisses Mexico Lawsuit Against Gun Manufacturers,” apnews.com, September 30, 2022, … Continue reading[63] Sarah Morland, “Mexico Launches Appeal in Suit Against U.S. Gun Makers,” reuters.com, March 16, 2023, … Continue reading

In 2021, ATF tracing of 20,916 firearms recovered in Mexico found that 67.5% were U.S.-sourced, meaning that the firearms that were either manufactured in the U.S. or legally imported into the U.S. by a federal firearms licensee. For the remaining weapons, 16.4% were of unknown origin and 16.1% were from a non-U.S. manufacturer without a known U.S. firearms importer (percentages are rounded).[64]Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, “Firearms Trace Data: Mexico - 2016-2021,” atf.gov, September 15, 2022, … Continue reading The ATF data only includes information on guns and ammunition confiscated by federal authorities and sent to ATF for tracing. It does not include tracing information on guns seized at the state level, guns that remain in circulation in Mexico and guns that have been trafficked via Mexico to neighboring countries in Central America.[65] Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking: US Efforts to Disrupt Gun Smuggling into Mexico Would Benefit from Additional Data and Analysis,” gao.gov, February 2021, … Continue reading An estimated 49% of guns recovered from crime scenes in El Salvador originated in the U.S., along with 45% of guns recovered in Honduras and 29% in Guatemala.[66] Chelsea Parsons and Eugenio Weigend Vargas, “Beyond Our Borders: How Weak US Gun Laws Contribute to Violent Crime Abroad,” americanprogress.org, February 2, 2018, … Continue reading

The ATF has found that most firearms in Mexico originating in the U.S. were acquired in a state along the southern border and purchased through the secondary market, meaning from pawn shops, internet sales, private collectors, or person-to-person transactions. [67] Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking: US Efforts to Disrupt Gun Smuggling into Mexico Would Benefit from Additional Data and Analysis,” gao.gov, February 2021, … Continue reading

Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), however, found that TCOs in Mexico were mainly using straw purchases to obtain guns, which is when a buyer purchases a gun for someone who is prohibited by law from possessing one or does not want their name associated with the transaction.[68]Dontlie.org, “Don’t Lie for the Other Guy,” atf.gov, accessed May 31, 2023, https://www.atf.gov/resource-center/docs/dontlie-postcard-enpdf/download[69]Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking: US Efforts to Disrupt Gun Smuggling into Mexico Would Benefit from Additional Data and Analysis,” gao.gov, February 2021, … Continue reading

Until President Joe Biden signed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act into law in June 2022, there were no federal laws strictly prohibiting firearms trafficking or straw purchases.[70]Joe Biden, “Remarks by President Biden at Signing of S.2938, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act,” whitehouse.gov, June 25, 2022, … Continue reading[71] Office of the Inspector General, “A Review of ATF’s Operation Fast and Furious and Related Matters,” oil.justice.gov, November 2012, https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2012/s1209.pdf Prior to 2022, other statutes such as 18 U.S.C. § 922(a)(1)(A) willfully engaging in firearms business without a license and 18 U.S.C. § 922(a)(6) knowingly making a false statement or presenting false identification in connection with a firearms purchase, were used to target arms trafficking and straw purchasers.[72]Office of the Inspector General, “A Review of ATF’s Operation Fast and Furious and Related Matters,” oil.justice.gov, November 2012, https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2012/s1209.pdf According to a spokesperson from the ATF in 2015, however, straw purchases were rarely prosecuted on their own because they can be difficult to prove and, if proven, judges rarely issued a severe punishment.[73]Alex Yablon, "Amid Dearth of Federal Action on Straw Buyers, States Forge Ahead on Their Own," thetrace.org, August 21, 2015, https://www.thetrace.org/2015/08/straw-purchases-law-atf-gun/ Data from the Government Accountability Office shows that 112,000 firearm purchases were denied in FY 2017 due to false information being provided on a federal firearms license application leading to 12,700 investigations by the ATF but only 12 convictions.[74]United States Government Accountability Office, "Law Enforcement: Few Individuals Denied Firearms Purchases Are Prosecuted and ATF Should Assess Use of Warning Notices in Lieu of Prosecutions," … Continue reading

Two of the four southern border states, California and New Mexico, have closed what’s known as the “gun show loophole” by requiring background checks for all sales at gun shows via state law.[75] Ben Garrett, “Gun Show Laws By State and the Gun Show Loophole,” thoughtco.com, January 2, 2021, https://www.thoughtco.com/gun-show-laws-by-state-721345 The other two states, Texas and Arizona, have no laws against the loophole, allowing private sales at gun shows to occur without background checks.[76] Ben Garrett, “Gun Show Laws By State and the Gun Show Loophole,” thoughtco.com, January 2, 2021, https://www.thoughtco.com/gun-show-laws-by-state-721345

The ATF attempted to trace the initial purchaser of 56,162 U.S.-sourced guns recovered in Mexico between 2014 and 2018, with a 50% success rate. When looking at all the recovered guns, 19% came from Texas, 9% from California, 8% from Arizona and 12% from all other U.S. states. Considering just the guns for which the original purchase location was found, 37% were bought in Texas, 18% in California, 16% in Arizona, 25% in all the other states and 5% had foreign purchasers.[77] Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking: US Efforts to Disrupt Gun Smuggling into Mexico Would Benefit from Additional Data and Analysis,” gao.gov, February 2021, … Continue reading

The U.S. Government Accountability Office stated that, “Trafficking of U.S.-sourced firearms into Mexico is a national security threat, as it facilitates the illegal drug trade and has been linked to organized crime.”[78] U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking: U.S. Efforts to Disrupt Gun Smuggling into Mexico Would Benefit from Additional Data and Analysis,” gao.gov, February 22, 2021, … Continue reading

V. U.S.-Mexico Efforts to Combat TCOs in the 21st Century

President George W. Bush assumed office in 2001 with an understanding of the importance of relations with Mexico, having served as a former governor of Texas, one of the four U.S. states along the shared border. [79] Arturo Sarukhan, “9/11 Transformed US-Mexico Relations,” brookings.edu, September 17, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/09/17/9-11-transformed-us-mexico-relations/His first international trip was a visit to the President of Mexico, Vicente Fox, in part to discuss border issues such as illegal drug trafficking.[80] Ramón Gutiérrez, “George W. Bush and Mexican Immigration Policy,” Revue Française d’Etudes Américaines, 2007/3 (No. 113), … Continue reading President Fox arrived in Washington in early September of 2001 to continue their negotiations on trade, immigration, and fighting crime at the border. Before any legislation could be drafted based on this summit, the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack in New York City (9/11) changed the national conversation about border security.

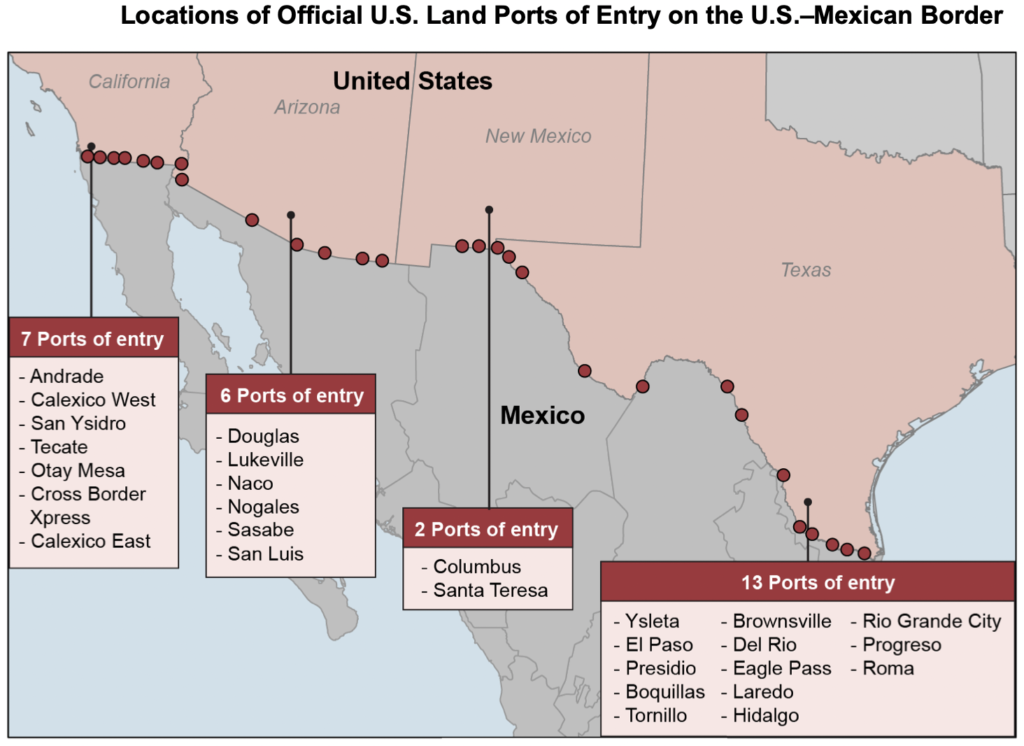

The U.S. shares a 1,954-mile border with Mexico across terrains that are difficult to patrol, including deserts, mountains, beaches, canyons and the Rio Grande River.[81] US Customs and Border Protection, “Border Wall System - Frequently Asked Questions,” cbp.gov, December 21, 2018, … Continue reading[82] United States Government Accountability Office, “Southwest Border: Information on Federal Agencies’ Process for Acquiring Private Land for Barriers,” democrats.senate.gov, November 2020, … Continue reading[83] Ioan Grillo, “Blood Gun Money: How America Arms Gangs and Cartels,” Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021 About 30% of the land on the U.S. side of the border is owned by the federal government while 70% is under state, tribal or private ownership. [84] United States Government Accountability Office, “Southwest Border: Information on Federal Agencies’ Process for Acquiring Private Land for Barriers,” democrats.senate.gov, November 2020, … Continue reading Border security tightened after 9/11 when the U.S. increased focus on stopping potential terrorists from entering via the southwest border, resulting in more inspectors and investigators at border stations, more aggressive border inspections, formalized entry requirements for all border crossings and the installation of fortified steel fences.[85] John Burnett, “The Security Crackdown After 9/11 Permanently Altered Life at the US-Mexico Border,” npr.org, September 9, 2021, … Continue reading[86] Stephen E. Flynn, "Rethinking the Role of the U.S. Mexican Border in the Post-9/11 World," cfr.org, March 23, 2004, https://www.cfr.org/report/rethinking-role-us-mexican-border-post-911-world[87] Stephen E. Flynn, "Rethinking the Role of the U.S. Mexican Border in the Post-9/11 World," cfr.org, March 23, 2004, https://www.cfr.org/report/rethinking-role-us-mexican-border-post-911-world[88] Héctor R. Ramírez Partida, "Post-9/11 U.S. Homeland Security Policy Changes and Challenges: A Policy Impact Assessment of the Mexican Front," NorteAmérica Volume 9, Issue 1, January-June … Continue reading[89] Paul Lewis, "A Wall Apart: Divided Families Meet at a Single, Tiny Spot on the US-Mexico Border," theguardian.com, March 29, 2016, … Continue reading

Image Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) data (February 2021)

Mexico and the U.S. signed the Action Plan for Cooperation and Border Security in 2002, aiming to combat organized crime, human smuggling, drug trafficking and migrant deaths. This plan eventually resulted in tightened security on the Mexican side of the border as well.[90] K. Larry Storrs, “Mexico-United States Dialogue on Migration and Border Issues, 2001-2005,” Congressional Research Service, June 2, 2005, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/RL32735.pdf A bigger step occurred in 2008, when the U.S. and Mexico signed the first Letter of Agreement for the Mérida Initiative.[91] OCAMPOMI, "The Mérida Initiative," mx.usembassy.gov, September 7, 2021, https://mx.usembassy.gov/the-merida-initiative/ This marked a shift towards shared responsibility for problems along the U.S.-Mexico border, recognizing both drug-related deaths in the U.S. and drug-related violence in Mexico.[92] Eric L. Olsen, "The Mérida Initiative and Shared Responsibility in US-Mexico Security Relations," The Wilson Quarterly, Winter 2017, … Continue reading The U.S. was charged with addressing demand for drugs and the guns and cash being smuggled through its southern border, while Mexico pledged to address government corruption.[93] Congressional Research Service, "Mexico: Evolution of the Mérida Initiative, FY2008-FY202," crsreports.congress.gov, last updated September 20, 2021, … Continue reading

President Barack Obama expanded the Mérida Initiative’s scope after taking office in 2009 by creating a four-pillar framework consisting of disrupting and dismantling crime organizations, institutionalizing the rule of law, taking a new approach to border security, and strengthening communities to reduce violence.[94] Eric L. Olsen, "The Mérida Initiative and Shared Responsibility in US-Mexico Security Relations," The Wilson Quarterly, Winter 2017, … Continue reading[95] Congressional Research Service, "Mexico: Evolution of the Mérida Initiative, FY2008-FY202," crsreports.congress.gov, last updated September 20, 2021, … Continue reading His approach garnered positive reactions from commentators who wanted to see more cooperation between the two countries, and criticism from those who thought the initiative should have retained its initial focus.[96] Congressional Research Service, "Mexico: Evolution of the Mérida Initiative, FY2008-FY202," crsreports.congress.gov, last updated September 20, 2021, … Continue reading

Via the Mérida Initiative, the U.S. spent $3.5 billion from FY 2008 to FY 2021 to modernize the Mexican Army, combat TCOs and disrupt the pipeline of northbound drugs.[97] Congressional Research Service,” U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation: From the Mérida Initiative to the Bicentennial Framework,” sgp.fas.org, updated December 12, 2022, … Continue reading The ATF and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) worked with their Mexican counterparts to improve firearm tracking, surveillance, and training.[98] The United States Department of Justice, “Fact Sheet: Department of Justice Efforts to Combat Mexican Drug Cartels,” justice.gov, April 2, 2009, … Continue reading The DEA employed a “kingpin” strategy that focused on targeting the heads of TCOs in the hope of disrupting their operations. This strategy resulted in Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s arrest in 2017 and transfer to the U.S. for sentencing.[99] Jessica Loudis, “El Chapo: What the Rise and Fall of the Kingpin Reveals About the War on Drugs,” theguardian.com, June 7, 2019, … Continue reading

The kingpin strategy, however, also led to fragmentation, localization and heightened intra-cartel violence, and ultimately did not disrupt TCOs pipelines. The cartels were able to overwhelm the Mexican Armed Forces with firepower and they sought retribution for fallen leaders.[100] Eduardo Giralt and Genevieve Kotarska, “The Kingpin Strategy: More Violence, No Peace,” rusi.org, NOvember 17, 2022, … Continue reading After El Chapo was extradited to the U.S., for example, 13 Mexican police officers died or went missing. El Chapo’s four sons stepped into their father’s shoes and built a fentanyl manufacturing and trafficking empire. In 2023, the U.S. put a $10 million bounty on two of the sons for information that will lead to their arrest.[101] Drazen Jorgic, “How El Chapo’s Sons Built a Fentanyl Empire Poisoning America,” reuters.com, May 9, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/mexico-drugs-chapitos/

The DEA’s tactics also backfired when agents let smaller crimes go with the intention of nailing a kingpin, such as in the Operation Fast and Furious scandal. In 2011, news broke that agents had allowed 2,000 guns to be trafficked into Mexico as part of the kingpin strategy; those guns were later used in crimes that included the murder of a Border Patrol agent.[102] Ioan Grillo, “Blood Gun Money: How America Arms Gangs and Cartels,” Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021

Fragmentation of TCOs has led to the creation of local splinter groups, franchised affiliates and local criminal gangs that were loosely affiliated with larger TCOs.[103] Chris Dalby, “How Mexico’s Cartels Have Learned Military Tactics,” insightcrime.org, September 2, 2021, https://insightcrime.org/news/how-mexicos-cartel-have-learned-military-tactics/ The resulting turf wars further incentivized TCOs to amass firepower and ammunition.[104] Eduardo Giralt and Genevieve Kotarska, “The Kingpin Strategy: More Violence, No Peace,” rusi.org, November 17, 2022, … Continue reading Ultimately, Mexico’s Foreign Minister deemed the Mérida initiative to be a failure because violence, drug trafficking and drug abuse continued to rise. The number of homicides in Mexico quadrupled from 2007 to 2021, and drug overdoses in the U.S. also skyrocketed.[105] Mary Beth Sheridan and Kevin Sieff, “Mexico Declares $3 Billion U.S. Security Deal ‘Dead,’ Seeks Revamp,” washingtonpost.com, July 29, 2021, … Continue reading

The Obama Administration also formed the National Southwest Border Counternarcotics Strategy (SWBCNS) in 2009, which focused on the U.S. side of the border and worked in conjunction with the Mérida Initiative to stem the flow of drugs into the U.S and the movement of illegal weapons and bulk cash from the U.S. into Mexico.[106] Office of National Drug Control Policy, “National Southwest Border Counternarcotics Strategy,” obamawhitehouse.archives.gov, 2011, … Continue reading ICE and DHS jointly patrolled the border, conducted sting operations, and targeted entry points into the U.S., including tunnel detection.[107]Office of National Drug Control Policy, “National Southwest Border Counternarcotics Strategy,” obamawhitehouse.archives.gov, 2011, … Continue reading

Even still, gun-related violence and deaths continued to rise across Mexico. According to a Congressional Research Services report, approximately 125,000-150,000 deaths in Mexico between 2006 and 2018 were attributed to organized crime, with an additional 73,000 people considered missing or disappeared.[108] June S. Beittel, “Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations,” crsreports.congress.gov, July 28, 2020, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R41576/45 Corruption in the Mexican government has also been cited by the U.S. government as a contributing factor to the increasing gun-related violence in Mexico this century, along with holes in U.S. border surveillance and inadequate agreements between the two countries for law enforcement operations.[109] United States Government Accountability Office, “Drug Control: U.S. Assistance Has Helped Mexican Counternarcotics Efforts, but Tons of Illicit Drugs Continue to Flow into the United … Continue reading

Within a month of taking office in 2017, President Donald Trump had issued two executive orders aimed at fighting TCOs and improving security at the southern border.[110]See: Executive Order 13767, 82 Fed. Reg. 8793 (January 25, 2017) and Executive Order 13773, 82 Fed. Reg. 10,691 (February 9, 2017) According to the Congressional Research Service, the Trump administration’s priorities included “reducing synthetic drug production, improving border interdiction and port security, and combating money laundering.”[111] Congressional Research Service, "Mexico: Evolution of the Mérida Initiative, FY2008-FY202," crsreports.congress.gov, last updated September 20, 2021, … Continue reading Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, elected in 2018, was a vocal critic of the Mérida Initiative and reportedly unwilling to attempt negotiations with Trump to revise the agreement. U.S.-Mexican relations were further strained when the U.S. government arrested a former Mexican defense minister for drug trafficking in October 2020.[112] Mary Beth Sheridan, “Facing Stunning Levels of Deaths, U.S. and Mexico Revamp Strained Security Cooperation,” Washington Post, October 8, 2021, … Continue reading

Under President Joe Biden, the U.S. and Mexico renewed their collaboration by announcing the Bicentennial Framework in October 2021.[113] Mary Beth Sheridan, “Facing Stunning Levels of Deaths, U.S. and Mexico Revamp Strained Security Cooperation,” Washington Post, October 8, 2021, … Continue reading The new cooperation agreement set goals to reduce substance abuse and crime in communities in both nations, prevent transborder crime such as drug and human trafficking, and disrupt TCO networks.[114] Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, “Fact Sheet The Mexico-U.S. Bicentennial Framework for Security, Public Health, and Safe Communities,” gob.mx, October 8, 2021, … Continue reading In March 2023, a joint statement from Mexico and the U.S. announced phase II of the Bicentennial Framework, which set out to “increase cooperation to combat illicit fentanyl production, the trafficking of high-caliber weapons and ammunition into Mexico, and transnational organized crime.”[115] The White House, “Joint Statement from Mexico and the United States on the Launch of Phase II of the Bicentennial Framework for Security,” whitehouse.gov, March 10, 2023, … Continue reading

VI. Conclusion

Efforts on the part of the CDC, Drug Enforcement Administration, and other federal agencies to reduce illegal substance usage and disrupt supply networks within the U.S. have not been successful. Nearly 200 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose.[116] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Understanding the Opioid Overdose Epidemic,” cdc.gov, last reviewed June 1, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/basics/epidemic.html Disrupting with the aim of destroying the well-established TCOs’ drug pipeline remains a necessity. With Mexican TCOs being the biggest synthetic opioid suppliers to the U.S., disrupting their operations across Mexico and in border towns is considered key to combating the opioid crisis. Unfortunately, two decades of joint efforts between Mexico and the U.S., which included military support, multiple federal agency support, and over $3 billion via the Mérida Initiative, have failed. Not only has the Mexican Army (heavily supported by the U.S. armed forces) not been able to combat the TCOs, but the gun-related violence in Mexico continues unabated, illegal substance trade into the U.S. continues unhindered, and the TCOs have emerged as a direct threat to Mexican democracy.

To date, the majority of the joint efforts have focused on disrupting the illicit drug trade: production activities in Mexico or cross-border drug trafficking. Even though there is recognition of how guns from the U.S. contribute to drug trafficking, solutions focus on disrupting gun trafficking, not disrupting gun purchasing.

Defining the problem in terms of a pipeline is also contributing to the lack of effective resolution. A pipeline of drugs entering the U.S. and a pipeline of guns entering Mexico has allowed the U.S. to disregard how lax gun laws in the U.S. contribute to drug trafficking. Recognizing that drugs-guns-drugs is a cycle where guns are purchased with the proceeds of the drug trade with the sole purpose of protecting all aspects of the drug trade, which in turn allows undisrupted drug trade, forces us to acknowledge the role U.S.’ lax gun laws play in this unfolding crisis. In 2010, Mexican President Calderón implored the U.S. Congress to reinstate the ban on assault rifles and increase regulation of gun sales in the U.S.,[117] Kasie Hunt, “Calderon Hits US from House Floor,” politico.com, May 20, 2010, https://www.politico.com/story/2010/05/calderon-hits-us-from-house-floor-037552 and in 2021, the Mexican government filed a civil suit against U.S. gun manufacturers for the damage their products were causing in Mexico.[118] Annika Kim Constantino, “Mexico Sues US Gun Companies, Alleging ‘Massive Damage’ That Is ‘Destabilizing’ to Society,” cnbc.com, August 4, 2021, … Continue reading

Sidetracked by the Second Amendment flashpoint, the U.S. continues to develop impotent solutions to combat the TCOs and disrupt drug supplies. But today, the need is greater than simply combating drug trafficking. As things stand, the TCOs are a serious threat to Mexican democracy, and there is a growing threat of spillover violence in the U.S. Moreover, as these illegal weapons move south into Central America and the Caribbean, they fuel violence and even increase the flow of asylum seekers at the U.S. southern border. To date, the U.S. government has decided against labeling TCOs as terrorist organizations due to their lack of political ideology. Even still, the government must continue to seek an effective way to protect U.S. citizens from the growing threat of drugs and gun violence.[119] Paul Rexton Kan, “El Chapo Bin Laden? Why Drug Cartels Are Not Terrorist Organizations,” icct.nl, February 4, 2020, … Continue reading[120] On March 29, 2023, Senator Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) introduced Senate Bill 1048 titled “A Bill To Designate Mexican Cartels and Other Transnational Criminal Organizations as Foreign Terrorist … Continue reading

References

| ↑1, ↑2 | Drug Enforcement Administration, “National Drug Threat Assessment,” justice.gov, March 2021, https://www.justice.gov/usao-mdpa/page/file/1425276/download |

|---|---|

| ↑3 | United States Government Accountability Office, “Drug Control: U.S. Assistance Has Helped Mexican Counternarcotics Efforts, but Tons of Illicit Drugs Continue to Flow into the United States,” gao.gov, August 2007, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-07-1018.pdf |

| ↑4 | Wilson Center Mexico Institute, “Mexico’s Role in the Deadly Rise of Fentanyl,” wilsoncenter.org, February 2019, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/fentanyl_insight_crime_final_19-02-11.pdf |

| ↑5, ↑13, ↑15 | Commission on Combating Synthetic Opioid Trafficking, “Final Report,” rand.org, February 8, 2022, https://www.rand.org/pubs/external_publications/EP68838.html |

| ↑6 | Tim Kaine, “Ernst, Kaine, Bice, Carbajal Introduce Bill to Combat Threat of Fentanyl,” kaine.senate.gov, May 16, 2023, https://www.kaine.senate.gov/press-releases/ernst-kaine-bice-carbajal-combat-threat-of-fentanyl |

| ↑7 | Brian Mann, “DEA moves to revoke major drug distributor’s license over opioid crisis failures,” NPR.org, May 26, 2023 |

| ↑8 | United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), “Fentanyl,” dea.gov, accessed May 29, 2023, https://www.dea.gov/factsheets/fentanyl |

| ↑9 | Claire Klobucista and Alejandra Martinez, “Fentanyl and the U.S. Opioid Epidemic,” cfr.org, April 19, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/fentanyl-and-us-opioid-epidemic |

| ↑10 | USA Facts, “Are Fentanyl Overdose Deaths Rising in the US?,” usafacts.org, December 9, 2022, https://usafacts.org/articles/are-fentanyl-overdose-deaths-rising-in-the-us/ |

| ↑11 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Understanding the Opioid Overdose Epidemic,” cdc.gov, last reviewed June 1, 2022, Why Can’t the U.S. and Mexico |

| ↑12 | Kaitlin Sullivan and Reynolds Lewis, “’A Staggering Increase’: Yearly Overdose Deaths Top 100,000 for First Time,” nbcnews.com, November 17, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/yearly-drug-overdose-deaths-top-100000-first-time-rcna5656 |

| ↑14 | Audrey Travère and Jules Giraudat, “Revealed: How Mexico's Sinaloa Cartel Has Created a Global Network to Rule the Fentanyl Trade,” theguardian.com, December 8, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/08/mexico-cartel-project-synthetic-opioid-fentanyl-drugs |

| ↑16 | Joseph J. Schleigh, “Statement of Joseph J. Schleigh, Acting Section Chief Synthetic Drugs and Chemicals Section Diversion Control Division Drug Enforcement Administration,” ussc.gov, December 5, 2017, https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/amendment-process/public-hearings-and-meetings/20171205/Schleigh.pdf |

| ↑17 | Anne Milgram, “Countering Illicit Fentanyl Trafficking,” Senate Committee on Foreign Relations hearing, February 15, 2023, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/f4597c23-de04-fa71-e612-bcbc49b6826c/021523_Milgram_Testimony.pdf |

| ↑18, ↑19 | National Drug Intelligence Center, “National Drug Threat Assessment 2009: Drug Trafficking Organizations,” justice.gov, December 2008, https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs31/31379/dtos.htm |

| ↑20, ↑33, ↑83, ↑102 | Ioan Grillo, “Blood Gun Money: How America Arms Gangs and Cartels,” Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021 |

| ↑21 | June S. Beittel, “Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations,” crsreports.congress.gov, July 28, 2020, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R41576/45 |

| ↑22, ↑108 | June S. Beittel, “Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations,” crsreports.congress.gov, July 28, 2020, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R41576/45 |

| ↑23 | Brennan Weiss, James Pasley, and Azmi Haroun, “Only 3 Countries in the World Protect the Right to Bear Arms in Their Constitutions: The US, Mexico, and Guatemala,” businessinsider.com, November 22, 2022, https://www.businessinsider.com/2nd-amendment-countries-constitutional-right-bear-arms-2017-10 |

| ↑24 | The third country is Guatemala. Ty McCormick, “How Many Countries Have Gun Rights Enshrined in Their Constitutions?,” foreignpolicy.com, April 5, 2013, https://foreignpolicy.com/2013/04/05/how-many-countries-have-gun-rights-enshrined-in-their-constitutions/ However, some sources also include Haiti, whose constitution reads, “Every citizen has the right to armed self-defense, within the bounds of this domicile, but has no right to bear arms without express well-founded authorization from the Chief of Police.” Constitute Project, “Haiti 1987 (rev. 2012),” constituteproject.org (accessed May 23, 2023), https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Haiti_2012?lang=en; |

| ↑25 | The original wording stated “are entitled to have arms of any kind in their possession,” but was altered when the constitution was revised in 1917. After this change, the right to bear arms was limited to the home. David B. Kopel, “Mexico’s Gun-Control Laws: A Model for the United States?,” SSRN Electronic Journal, April 2010, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/43015235_Mexico's_Federal_Law_of_Firearms_and_Explosives |

| ↑26 | National Constitution Center, “The United States Constitution,” constitutioncenter.org, accessed May 25, 2023, https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/full-text |

| ↑27 | Jonathan Masters, “How Do US Gun Laws Compare to Other Countries?,” pbs.org, November 17, 2017, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/how-do-u-s-gun-laws-compare-to-other-countries |

| ↑28 | Philip Alpers and Miles Lovell, “Mexico — Gun Facts, Figures and the Law,” gunpolicy.org, December 7, 2022, https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/region/mexico |

| ↑29 | FindLaw, “Gun Laws,” findlaw.com, December 27, 2022, https://www.findlaw.com/injury/product-liability/gun-laws.html |

| ↑30 | Many sources state that Mexico has only one gun store, but there may be a satellite store also run by the military serving just three states in the northeast of the country, known as O.T.C.A. (Las Oficinas para Trámites de Comercialización de Artículos). We emailed the Mexican government on May 25, 2023, requesting verification of the number of stores. |

| ↑31 | Wilma Gandoy Vázquez and Ximena García Hidalgo, “Mexico’s Bold Move Against Gun Companies,” Arms Control Association, September 2022, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2022-09/features/mexicos-bold-move-against-gun-companies |

| ↑32, ↑38 | Audrey Carlsen and Sahil Chinoy, “How to Buy a Gun in 16 Countries,” nytimes.com, August 6, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/03/02/world/international-gun-laws.html |

| ↑34 | MexLaw, “Some Basic Facts About Gun Control in Mexico,” mexlaw.com, accessed May 25, 2023, https://mexlaw.com/some-basic-facts-about-gun-control-in-mexico-2/ |

| ↑35 | Armas MX, “¿Como Adquirir un arma en México?,” armasmx.com, accessed May 25, 2023, https://www.armasmx.com/compra-de-armas |

| ↑36 | United States Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, “Report of Active Firearms Licenses - License Type by State Statistics,” atf.gov, April 10, 2023, https://www.atf.gov/firearms/listing-federal-firearms-licensees/complete?field_ffl_date_value%5Bvalue%5D%5Byear%5D=2023&ffl_date_month%5Bvalue%5D%5Bmonth%5D=4 |

| ↑37 | Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, “Brady Law,” atf.gov, July 2021, https://www.atf.gov/rules-and-regulations/brady-law |

| ↑39 | Giffords, “Universal Background Checks,” giffords.org, accessed May 29, 2023, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/gun-laws/policy-areas/background-checks/universal-background-checks/ |

| ↑40 | Rand Corporation, “The Effects of Background Checks,” rand.org, January 10, 2023, https://www.rand.org/research/gun-policy/analysis/background-checks.html |

| ↑41 | Matthew Miller, Lisa Hepburn and Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Acquisition Without Background Checks,” Annals of Internal Medicine, February 21, 2017, https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M16-1590 |

| ↑42 | Joseph Stepansky, "U S Lawmakers Banned Assault Weapons in 1994. Why Can't They Now?" aljazeera.com, April 20, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/4/20/us-legislators-banned-assault-weapons-in-94-why-cant-they-now |

| ↑43 | Giffords Law Center, "Assault Weapons in Arizona," giffords.org, last updated January 3, 2023, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/state-laws/assault-weapons-in-arizona/ |

| ↑44 | Giffords Law Center, "Assault Weapons in New Mexico," giffords.org, last updated January 5, 2023, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/state-laws/assault-weapons-in-new-mexico/ |

| ↑45 | Giffords Law Center, "Assault Weapons in Texas," giffords.org, last updated January 3, 2023, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/state-laws/assault-weapons-in-texas/ |

| ↑46 | Giffords Law Center, "Assault Weapons in California," giffords.org, last updated January 3, 2023, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/state-laws/assault-weapons-in-california/ |

| ↑47 | New World Encyclopedia, “Mexican War of Independence,” newworldencyclopedia.org (accessed June 2, 2023), https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Mexican_War_of_Independence |

| ↑48, ↑49, ↑52, ↑55, ↑65, ↑67, ↑77 | Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking: US Efforts to Disrupt Gun Smuggling into Mexico Would Benefit from Additional Data and Analysis,” gao.gov, February 2021, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-322.pdf |

| ↑50 | Conor Finnegan, “Gun used in kidnapping, killing of Americans in Mexico came from US,” abcnews.go.com, March 21, 2023, https://abcnews.go.com/International/gun-kidnapping-americans-mexico-allegedly-us/story?id=98012006 |

| ↑51 | Liz Mineo, “Stopping Toxic Flow of Guns from U.S. to Mexico,” news.harvard.edu, February 18, 2022, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2022/02/stopping-toxic-flow-of-gun-traffic-from-u-s-to-mexico/ |

| ↑53 | Donald Trump, “Enforcing Federal Law with Respect to Transnational Criminal Organizations and Preventing International Trafficking,” federalregister.gov, February 9, 2017, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/02/14/2017-03113/enforcing-federal-law-with-respect-to-transnational-criminal-organizations-and-preventing |

| ↑54 | Chris McGreal, “How Mexico's Drug Cartels Profit from Flow of Guns Across the Border,” theguardian.com, December 8, 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/dec/08/us-guns-mexico-drug-cartels |

| ↑56 | Topher McDougal, et al., "The Way of the Gun: Estimating Firearms Traffic Across the U.S.-Mexico Border," IGARAPE Institute, University of San Diego Trans-Border Institute, March 2023, https://igarape.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Paper_The_Way_of_the_Gun_web2.pdf |

| ↑57 | Christopher Ingraham, “Why Mexico’s Drug Cartels Love America’s Gun Laws,” washingtonpost.com, January 14, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/01/14/why-mexicos-drug-cartels-love-americas-gun-laws/ |

| ↑58 | United States Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, “Report of Active Firearms Licenses - License Type by State Statistics,” atf.gov, May 10, 2023, https://www.atf.gov/firearms/docs/undefined/0523-ffl-list-type-statepdf/download |

| ↑59 | Al Jazeera, “US Judge Dismisses Mexico’s $10bn Lawsuit Against Gun Makers,” aljazeera,com, October 1, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/10/1/us-judge-dismisses-mexicos-10bn-lawsuit-against-gun-makers |

| ↑60, ↑61 | United States of Mexico, “Estados Unidos Mexicanos v. Smith & Wesson Brands, Inc.; Barrett Firearms Manufacturing, Inc.; Beretta U.S.A. Corp., et al.,” August 4, 2021 |

| ↑62 | AP News, “US Judge Dismisses Mexico Lawsuit Against Gun Manufacturers,” apnews.com, September 30, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/business-mexico-caribbean-lawsuits-gun-politics-441dece6a6ff8adb7b222e7d8e7d6286 |

| ↑63 | Sarah Morland, “Mexico Launches Appeal in Suit Against U.S. Gun Makers,” reuters.com, March 16, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/mexico-launches-appeal-suit-against-us-gun-manufacturers-2023-03-16/#:~:text=A%20U.S.%20judge%20in%20September,deadly%20weapons%20across%20the%20border |

| ↑64 | Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, “Firearms Trace Data: Mexico - 2016-2021,” atf.gov, September 15, 2022, https://www.atf.gov/resource-center/firearms-trace-data-mexico-2016-2021 |

| ↑66 | Chelsea Parsons and Eugenio Weigend Vargas, “Beyond Our Borders: How Weak US Gun Laws Contribute to Violent Crime Abroad,” americanprogress.org, February 2, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/beyond-our-borders/ |

| ↑68 | Dontlie.org, “Don’t Lie for the Other Guy,” atf.gov, accessed May 31, 2023, https://www.atf.gov/resource-center/docs/dontlie-postcard-enpdf/download |

| ↑69 | Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking: US Efforts to Disrupt Gun Smuggling into Mexico Would Benefit from Additional Data and Analysis,” gao.gov, February 2021, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-322.pdf |

| ↑70 | Joe Biden, “Remarks by President Biden at Signing of S.2938, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act,” whitehouse.gov, June 25, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/06/25/remarks-by-president-biden-at-signing-of-s-2938-the-bipartisan-safer-communities-act/ |

| ↑71 | Office of the Inspector General, “A Review of ATF’s Operation Fast and Furious and Related Matters,” oil.justice.gov, November 2012, https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2012/s1209.pdf |

| ↑72 | Office of the Inspector General, “A Review of ATF’s Operation Fast and Furious and Related Matters,” oil.justice.gov, November 2012, https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2012/s1209.pdf |

| ↑73 | Alex Yablon, "Amid Dearth of Federal Action on Straw Buyers, States Forge Ahead on Their Own," thetrace.org, August 21, 2015, https://www.thetrace.org/2015/08/straw-purchases-law-atf-gun/ |

| ↑74 | United States Government Accountability Office, "Law Enforcement: Few Individuals Denied Firearms Purchases Are Prosecuted and ATF Should Assess Use of Warning Notices in Lieu of Prosecutions," GAO-18-440, gao.gov, September 5, 2018, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-18-440 |

| ↑75, ↑76 | Ben Garrett, “Gun Show Laws By State and the Gun Show Loophole,” thoughtco.com, January 2, 2021, https://www.thoughtco.com/gun-show-laws-by-state-721345 |

| ↑78 | U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking: U.S. Efforts to Disrupt Gun Smuggling into Mexico Would Benefit from Additional Data and Analysis,” gao.gov, February 22, 2021, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-322 |

| ↑79 | Arturo Sarukhan, “9/11 Transformed US-Mexico Relations,” brookings.edu, September 17, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/09/17/9-11-transformed-us-mexico-relations/ |

| ↑80 | Ramón Gutiérrez, “George W. Bush and Mexican Immigration Policy,” Revue Française d’Etudes Américaines, 2007/3 (No. 113), https://www.cairn.info/revue-francaise-d-etudes-americaines-2007-3-page-70.htm |

| ↑81 | US Customs and Border Protection, “Border Wall System - Frequently Asked Questions,” cbp.gov, December 21, 2018, https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/border-wall/border-wall-system-frequently-asked-questions |

| ↑82, ↑84 | United States Government Accountability Office, “Southwest Border: Information on Federal Agencies’ Process for Acquiring Private Land for Barriers,” democrats.senate.gov, November 2020, https://www.democrats.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/GAO%20-%20Information%20on%20Federal%20Agencies'%20Process%20for%20Acquiring%20Private%20Land%20for%20Barriers.pdf |

| ↑85 | John Burnett, “The Security Crackdown After 9/11 Permanently Altered Life at the US-Mexico Border,” npr.org, September 9, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/09/09/1035610401/the-security-crackdown-after-9-11-permanently-altered-life-at-the-u-s-mexico-bor |

| ↑86, ↑87 | Stephen E. Flynn, "Rethinking the Role of the U.S. Mexican Border in the Post-9/11 World," cfr.org, March 23, 2004, https://www.cfr.org/report/rethinking-role-us-mexican-border-post-911-world |

| ↑88 | Héctor R. Ramírez Partida, "Post-9/11 U.S. Homeland Security Policy Changes and Challenges: A Policy Impact Assessment of the Mexican Front," NorteAmérica Volume 9, Issue 1, January-June 2014, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1870355014701132 |

| ↑89 | Paul Lewis, "A Wall Apart: Divided Families Meet at a Single, Tiny Spot on the US-Mexico Border," theguardian.com, March 29, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/mar/29/us-mexico-border-wall-trump-cruz-immigration-friendship-park |

| ↑90 | K. Larry Storrs, “Mexico-United States Dialogue on Migration and Border Issues, 2001-2005,” Congressional Research Service, June 2, 2005, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/RL32735.pdf |

| ↑91 | OCAMPOMI, "The Mérida Initiative," mx.usembassy.gov, September 7, 2021, https://mx.usembassy.gov/the-merida-initiative/ |

| ↑92 | Eric L. Olsen, "The Mérida Initiative and Shared Responsibility in US-Mexico Security Relations," The Wilson Quarterly, Winter 2017, https://www.wilsonquarterly.com/quarterly/_/the-m-rida-initiative-and-shared-responsibility-in-u-s-mexico-security-relations |

| ↑93, ↑95, ↑96, ↑111 | Congressional Research Service, "Mexico: Evolution of the Mérida Initiative, FY2008-FY202," crsreports.congress.gov, last updated September 20, 2021, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10578/21 |

| ↑94 | Eric L. Olsen, "The Mérida Initiative and Shared Responsibility in US-Mexico Security Relations," The Wilson Quarterly, Winter 2017, https://www.wilsonquarterly.com/quarterly/_/the-m-rida-initiative-and-shared-responsibility-in-u-s-mexico-security-relations |

| ↑97 | Congressional Research Service,” U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation: From the Mérida Initiative to the Bicentennial Framework,” sgp.fas.org, updated December 12, 2022, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/IF10578.pdf |

| ↑98 | The United States Department of Justice, “Fact Sheet: Department of Justice Efforts to Combat Mexican Drug Cartels,” justice.gov, April 2, 2009, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/fact-sheet-department-justice-efforts-combat-mexican-drug-cartels |

| ↑99 | Jessica Loudis, “El Chapo: What the Rise and Fall of the Kingpin Reveals About the War on Drugs,” theguardian.com, June 7, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/07/el-chapo-the-last-of-the-cartel-kingpins |

| ↑100 | Eduardo Giralt and Genevieve Kotarska, “The Kingpin Strategy: More Violence, No Peace,” rusi.org, NOvember 17, 2022, https://shoc.rusi.org/blog/the-kingpin-strategy-more-violence-no-peace/ |

| ↑101 | Drazen Jorgic, “How El Chapo’s Sons Built a Fentanyl Empire Poisoning America,” reuters.com, May 9, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/mexico-drugs-chapitos/ |

| ↑103 | Chris Dalby, “How Mexico’s Cartels Have Learned Military Tactics,” insightcrime.org, September 2, 2021, https://insightcrime.org/news/how-mexicos-cartel-have-learned-military-tactics/ |

| ↑104 | Eduardo Giralt and Genevieve Kotarska, “The Kingpin Strategy: More Violence, No Peace,” rusi.org, November 17, 2022, https://shoc.rusi.org/blog/the-kingpin-strategy-more-violence-no-peace/ |

| ↑105 | Mary Beth Sheridan and Kevin Sieff, “Mexico Declares $3 Billion U.S. Security Deal ‘Dead,’ Seeks Revamp,” washingtonpost.com, July 29, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/07/29/mexico-merida-initiative-violence/ |

| ↑106 | Office of National Drug Control Policy, “National Southwest Border Counternarcotics Strategy,” obamawhitehouse.archives.gov, 2011, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/swb_counternarcotics_strategy11.pdf |

| ↑107 | Office of National Drug Control Policy, “National Southwest Border Counternarcotics Strategy,” obamawhitehouse.archives.gov, 2011, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/swb_counternarcotics_strategy11.pdf |

| ↑109 | United States Government Accountability Office, “Drug Control: U.S. Assistance Has Helped Mexican Counternarcotics Efforts, but Tons of Illicit Drugs Continue to Flow into the United States,” gao.gov, August 2007, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-07-1018.pdf |

| ↑110 | See: Executive Order 13767, 82 Fed. Reg. 8793 (January 25, 2017) and Executive Order 13773, 82 Fed. Reg. 10,691 (February 9, 2017) |

| ↑112, ↑113 | Mary Beth Sheridan, “Facing Stunning Levels of Deaths, U.S. and Mexico Revamp Strained Security Cooperation,” Washington Post, October 8, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/10/08/mexico-merida-initiative-security/ |

| ↑114 | Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, “Fact Sheet The Mexico-U.S. Bicentennial Framework for Security, Public Health, and Safe Communities,” gob.mx, October 8, 2021, https://www.gob.mx/sre/documentos/fact-sheet-the-mexico-u-s-bicentennial-framework-for-security-public-health-and-safe-communities |

| ↑115 | The White House, “Joint Statement from Mexico and the United States on the Launch of Phase II of the Bicentennial Framework for Security,” whitehouse.gov, March 10, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/03/10/joint-statement-from-mexico-and-the-united-states-on-the-launch-of-phase-ii-of-the-bicentennial-framework-for-security/ |

| ↑116 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Understanding the Opioid Overdose Epidemic,” cdc.gov, last reviewed June 1, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/basics/epidemic.html |

| ↑117 | Kasie Hunt, “Calderon Hits US from House Floor,” politico.com, May 20, 2010, https://www.politico.com/story/2010/05/calderon-hits-us-from-house-floor-037552 |

| ↑118 | Annika Kim Constantino, “Mexico Sues US Gun Companies, Alleging ‘Massive Damage’ That Is ‘Destabilizing’ to Society,” cnbc.com, August 4, 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/08/04/mexico-sues-us-gun-manufacturers-alleging-they-cause-massive-damage-to-country.html |

| ↑119 | Paul Rexton Kan, “El Chapo Bin Laden? Why Drug Cartels Are Not Terrorist Organizations,” icct.nl, February 4, 2020, https://www.icct.nl/publication/el-chapo-bin-laden-why-drug-cartels-are-not-terrorist-organisations |

| ↑120 | On March 29, 2023, Senator Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) introduced Senate Bill 1048 titled “A Bill To Designate Mexican Cartels and Other Transnational Criminal Organizations as Foreign Terrorist Organizations and Recognizing the Threats Those Organizations Pose to the People of the United States as Terrorism, and for Other Purposes,” - short title: Ending the Narcos Act of 2023. At the time of writing this report, the bill has been read twice and referred to the Select Committee on Intelligence. |